ABSTRACT:

Over the years, various attempts at developing a comprehensive knowledge management framework have identified that one of the key functions in creating knowledge assets is the task of selecting or filtering public domain knowledge in order to make it relevant to the organization. This paper discusses the nature of the filtering step in order to define a sound knowledge management approach.

1. Introduction

Faced with a bombardment of Electronic Mail, Web pages and reports on a daily basis, how does someone determine which items to accept and retain, and which to ignore or reject? In the context of knowledge management, this selection can be defined as a filtering process which is made by the knowledge worker or potentially an automated system. By many, it is perceived to be the activities with the highest return on investment in a Knowledge Management program, but also one of the most challenging.

As decision makers, not only are we being overwhelmed with information, we are frequently confronted with conflicting information. Information disparities become irritating if not dangerous when that information is the basis for a major social, political or business decisions. Our normal approach to resolving these conflicts is usually to establish the value of each piece of information and decide on the basis of the one which is more suited to our pursuit of an answer.

This behaviour is a learned behaviour. We have been taught throughout our management training, that sound decisions are based on facts and judgement of the facts. Some are informational facts, others are the tools for interpreting the information, or the available knowledge assets.

The underlying theory of knowledge management is that you can accumulate knowledge assets (Brooking, 1996) and use them effectively to gain a competitive advantage.

Knowledge assets will take various forms such as : Markets reach, Employee expertise, Intellectual property and infrastructures such as organization, processes, systems and methods.

Knowledge assets (Phaneuf et al, 1996) are created by acquiring knowledge in various forms of information from the environment, making this information meaningful and useful to the employees and actors in such a manner that it can be converted into methods, know how or business rules which will enable the organization to meet its goals. As such it is not the knowledge which gives the competitive edge, but the capacity to transform knowledge into competencies (Phaneuf et al, 1996) and replicable know-how.

Achieving results in knowledge management is the product of a two fold evolution of an existing knowledge : its enhancement (depth) and its transfer (application). Some of the choices made on retaining or rejecting information which represent knowledge consequently play a key role in the availability and usability of knowledge within and organization. Holsapple and Joshi (1998) have termed the second step in the knowledge management activities as the "filtering" or knowledge selection process.

"Selecting knowledge refers to the activity of identifying needed knowledge within an organization's available knowledge resources and providing it in an appropriate representation to an activity that needs it". It is the contention of these authors that selection is differentiated from knowledge acquisition on the basis that acquisition deals with identifying and capturing available information in the environment, while filtering is a systemic process applied to information which is already available to the organizational.

2. Making Sense Out of Data and Knowledge

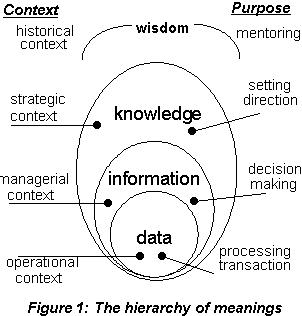

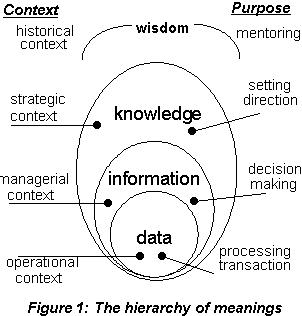

Prior to addressing the details of the filtering processes, it may be important to distinguish between data, information and knowledge. Figure 1 illustrates the continuum which serves as a point of departure of most of our reflection on the relationship between data, information and knowledge. In summary, the difference associated with each stems from two things, one is the purpose and the other one is the context. Purpose relates to the cause which gave birth to the object while the context gives it its relative value to the user.

Data constitutes one of the primary form of information. It essentially consists of recordings of transactions or events which will be used for exchange between humans or even with machines. As such, data does not carry meaning unless one understands the context in which the data was gathered. A word, a number or a symbol can be used do describe a business result, inserted in a marriage contract or a graffiti on the wall. It is the context which gives it meaning, and this meaning makes it informative.

Information extends the concept of data in a broader context. As such it includes data but it also includes all the information a person comes in contact with as a member of a social organization in a given physical environment. Information like data, is carried through symbols. These symbols have complex structures and rules. Information therefore comes in a variety of forms such as writings, statements, statistics, diagrams or charts. Some information theorists insist on the concept of form as the differentiating factor and the essence of information.

Where does knowledge fit in this scenario? Information becomes individual knowledge when it is accepted and retained by an individual as being a proper understanding of what is true (Lehrer, 1990) and a valid interpretation of the reality. Conversely, organizational or social knowledge exists when it is accepted by a consensus of a group of people. Common knowledge does not require necessarily to be shared by all members to exist, the fact that it is accepted amongst a group of informed persons can be considered a sufficient condition. This is also true of «public domain» knowledge. The fact that it is readily available in writing or published material does not entail that everybody should be knowledgeable about it to meet the condition of being "common knowledge".

Where information becomes knowledge can be difficult to perceive because we tend to perceive the existence of knowledge through information. Information represent artefacts of knowledge, means though which a significant portion of knowledge is circulated, shared or transacted between individuals, organizations and even transferred between societies.

For the purpose of defining a sound management process for knowledge assets, this only increases the complexity of separating the wheat from the chaff in order to retain the valuable and relevant information. But why are some pieces of information accepted and retained as appropriate representations of relevant knowledge, whereas other information is rejected or ignored? Mainly because there are human rules which give the context its nature and character.

3. Filtering Systems

3.1 Discussion

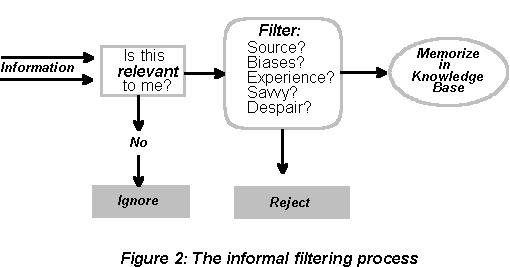

Knowledge theory, whether from the psychological, the biological or philosophical perspective have one element in common: knowledge is acquired through a selection or filtering process. Animals as well as person uses a filtering process (Plotkin, 1994) that determines which pieces of information to retain. The decision to retain or to reject depends mainly on the perception of the relevance of the information in the immediate context. The basic components of such a process are depicted in Figure 2. In the model, the receiver is described as the person who must decide which pieces of information to add to the reservoir of knowledge called «knowledge base».

The initial factor determining which pieces of general information will be assessed is the relevancy of that information to the receiver. Relevancy also means that people will be more attentive to information related to their areas of interest or to the problem which currently draws their attention.

This does not mean receivers "completely" ignore non-relevant information. Some of it may be retained, at a subconscious level and recalled from memory as needed. In general, most people do not make a conscious effort to assess or retain it. As a result, persons with varied interests, will tend to record a broader range of information that is perceived as being relevant.

Relevancy (Kress, 1993) of the information is the result of an appreciation of the information.

The observation of day to day behaviour of managers have lead to the identification of a certain number of these factors which influence the filtering process:

3.2 Authority/Creditability of Source of Information

The receiver is normally better disposed towards information that comes from an authoritative source. Our individual experience has formed different patterns of authority in our system of appreciation. In an organizational context, authority is imbedded in the structure, the division of work and the jurisdiction. As a result, we tend to associate our perception of «knowledgeability» with the distribution of authority within the organization. Policy information originating from headquarters bears more weight than the same information coming from the district office.

To offset the credibility gap, many organizations have resorted to the use of filtering experts who add the seal of authority to information artefacts. Researchers and documentation analysts by "reviewing" incoming information act as official filters and may on occasion give value to otherwise trivial information.

3.3 Organizational Biases

The term bias implies a closed-mindedness or a prejudicial outlook that prevents someone from judging the situation in an objective manner. The key here remains the opposition we tend to make between the concept of objective and the concept of subjectivity or bias. Most individuals brought up in the judeo-christian education have been taught a behaviour which consists in accepting information that is in agreement with our personal beliefs, and of questioning opposing information (Troelsch, 1931). The more advanced the education the more socially acceptable the questioning. Organizations tend to emulate the same behaviour by opening or closing themselves to external influences.

The organizational biases translates into summary judgement whose function is to reinforce our beliefs. Beliefs do not have to be truths, they therefore do not qualify as knowledge, but they are an integral part of our appreciative system and act as filtering agents in knowledge retention.

3.4 Corporate Historical Context

In a similar manner, we will tend to accept information that reinforces our personal experiences. The process is essentially the same as in the case of beliefs. The difference lies in the past experience as opposed to an interpretative construct. Similarly we tend to reject information, regardless of the source, which contradict our understanding of history, even more so when it is our own.

This behaviour is commonly observed in organizations which reinforce positive behaviour through reward systems. As a result, business units and business systems tend to accept information which follows a predictable pattern more easily than information which disrupts a pattern.

3.5 Receiver's Savvy

Formal education is still a process of acquisition of large amounts of information and concepts. There is a social consensus that backgrounds in a variety of arts, culture or scientific domain will enable a person to draw on a broader base of reference models when evaluating information. These reference models are important because they constitute a means of organizing incoming information and establishing relationship between events, information sources and persons.

The savvy factor can be seen as the skills of the individual or organizations who acts as receiver and conducts the initial assessment of the information. A community or a person who understands proper research procedures, is better able to assess information obtained by surveys. People who are familiar with the basics of a science or a discipline, can more readily make sense out of otherwise disparate pieces of information. Knowledgeable receivers tend therefore to make better use of information.

3.5 Desperation Factor

For most managers, the reality of management is conditioned by the availability of factual data and measurable results. "Something beats nothing !" This is true for most persons educated in the Western set of values. As a result, the same manager becomes desperate when some crucial information cannot be found. Under these circumstances he or she will accept almost anything that seems pertinent.

Available knowledge in an organizational environment, and particularly corporate knowledge is the product of a series of human decision along a chain of events which brought pieces of information into contact with the organization. The more one analyses the organizational context, the less it becomes a purely rational and objective construct. How we do things in the corporation reflects not only what we know but also what we have chosen to know; conversely, smarter organizations have better know-how.

4. Filtering Behaviour

The discussion on human filtering above is intended to provide a framework for developing an approach to the systematic performance of filtering in knowledge management. With the exponential growth of data and information artefacts, one can easily perceive the added value of an effective filtering process. Without such a process knowledge workers are flooded with information and spend more energy sorting out the information than in making it useful to their job.

Based on observations of best practices, our contention is that the design of a formal filtering process will requires two steps:

The knowledge artefacts which pass the filter test will eventually become part of the knowledge base. At that point the statements retained will have both relevance and the interpretative attributes. They will be considered true and the receiving organization will believe that it is right in considering these statements to be true.

When one considers the human behaviour which the knowledge management process is trying to emulate, one must realize that the quality of these filtering processes varies, not only between receivers, but also at different times for the same receiver and in different social environments perceived by the same receiver. It would be difficult therefore to state that there is a «one best way» which will apply equally to all organizations.

Recognizing the «social» or organizational dimension of knowledge is at the core of any sustainable solution to managing corporate knowledge. What we know about the individual mind needs to be reinterpreted in the context of the collective mind. Organizations remain solutions of compromises to achieve a balance with their environment on the basis of their know how. Imperfect information, adherence to truths and beliefs are part of the compromise. This is why the simple relevance factor is not a sufficient condition, it must also become part of the copororate culture, become a segment of the organizational reality and acquire value through the appreciative processes.

5. Knowledge Appreciation Practices

Up to now, we have described how the information is processed by an individual or a group in the context of «storing it in a knowledge base». Our proposed model actually describes how externally provided information can be integrated into the working environment as relevant sources of explicit knowledge.

Litteraly taken, the model would entail that organizations which accumulate large quantity of relevant information would acquire a competitive edge. There are numerous examples of small focused organizations which can serve as a counter-example. The difference rests in the practical application of the available knowledge or in the actual know how. Whenever the knowledge is expected to become part of the organizational know how and the information will subsequently play a major role in an important decision, a more formal appreciative procedure will be required by most organizations.

Because knowledge artefacts are transmitted as pieces of information, the quality of explicit knowledge is determined by it's accuracy and appropriateness. Knowledge itself will be qualified through its relevance and purpose. The implementation of these attributes to a knowledge artefact will be mediated by its informational content. Information is accurate when it describes the actual situation though consistent and perceivable attributes. Knowledge is appropriate when it can be used to interpret the reality and provide a mean of predicting the behaviour of resources, people or systems. While the attributes of information are descriptive, the attributes of knowledge are interpretative. One provides the values, the latter the reference framework. In practical terms, know how is relevant when it meets the needs of a community of receivers for sharing a common interpretation of "how the reality can be transformed". Between accuracy and appropriateness of knowledge artefacts it is usually easier to assess the last. Appreciation essentially is effected by placing a value on the relevance of the knowledge artefact given a specific context. It is only a multivariate judgement call. These attributes tend to fall into certain categories as follows.

5.1 Time Relevance Factor

Knowledge artefacts have place in time and a life cycle. There are times where a knowledge artefact will better serve its purpose. Situating the artefact in the proper step of its life cycle will establish its time relevance.

5.2 Actor Relevance Factor

Filtering will associate the information with a targeted user or a community of knowledge workers. Actor relevance may therefore vary depending on the intended audience.

5.3 Technical Relevance Factor

Documents serve different purposes. Filtering for technical relevance implies establishing the likelihood of usefulness for a community of users or for a «knowledge centre». If the representation of knowledge can be the source of a know-how for the intended community, it carries the attribute of technical relevance.

5.4 Authority Factor

Ideally all information would be accompanied by an audit or "seal of approval" attesting to it's accuracy.

Filtering processes associated with authority are closely related to quality assurance of knowledge artefacts. It requires standards against which the information will need to be assessed. It would be difficult to build a filtering process which would not be based on filtering criteria developed in partnership with experts.

5.5 Fidelity Factor

One of the other factors to consider is how important is it that the knowledge artefact contains a sufficient amount of details to depict the state of the knowledge.

There is therefore a judgement call made by the individual executing the filtering about the degree of comprehensiveness and validity of the information for the intended purpose. Such judgement is difficult remains a fuzzy logic derived from perceptions of anticipated future use of the knowledge artefacts.

5.6 Scientific Acceptability Factor

Once a piece of information has been identified as relevant, the problems becomes to ensure that it is an acceptable knowledge artefact.

Scientific validity is a bone of contention merely because science evolves at a rapid pace. Only rarely will a knowledge manager possess the scientific refinement to make such a judgement call. Most of the time, the intended user of the subject matter experts will be the only available resource to make a decision. One can expect that the scientific validity of knowledge artefacts will likely remain the domain of the specialist. Effectiveness of knowledge management practices cannot be achieved without the involvement of the user.

6. A Matter of Appreciative Capacity Building

In designing KM practices we have observed that systemic filtering of information creates attributes of relevance, and relevance creates useful knowledge. Useful knowledge in turn tests the limits of the organizational compromise and stimulates conditions of a higher level of performance. It is not the knowledge which is competitive it is the know how that is derived from appreciating its relevance.

But not all organizations are created equal. Organizations will effectively allocate different quality and level of resources over time to the process. Differences may be in the level of service, quality of sources and technical development of systems. This results in qualitative differences in the construction of the knowledge base, and different degree of sophistication in the available explicit knowledge.

The result is different degrees of capabilities to manage knowledge. In business related topics, the source' s authority usually prevails. Our bureaucratic authority models have conditioned us to accept that policies take precedence over individual whim. To a certain extend, corporate moods and emotions are reflected by fads and fashionable concepts which in turn bring to the forefront of the corporate life transient values and modify the relative importance of principles, concepts and sometimes truth. As a result, some organizations are more «learned» than others and better predisposed to managing their knowledge assets than others. Organizations with a long history of imitative pursuit of the silver bullet may be difficult candidates.

Contrary to the human knowledge base which consists of virtually

limitless memory and structuration (Polanyi, 1962), corporate

knowledge bases are bound by physical constraints of space, time

and human resources. As a consequence, the management of the life

cycle of the knowledge resource becomes part of the success formula.

While many believe that corporate knowledge may be organized and

compiled in a set of durable statements or business rules, most

of the practitioners of artificial intelligence have come to state

the obvious: in a business context truth is transient and contextual.

"One man's truth is the other's fallacy" has

been the cornerstone of inter-cultural as well as inter-organizational

relations. Failing to recognize the phenomenon will normally led

to the use of the wrong rules to fight the right problem, or more

frequently disregarding the problem because it cannot be addressed

with the exiting set of rules.

Another factor affecting the filtering competency is the importance which the organization gives to the efficiency or effectiveness of the filtering process itself. Although the initial screen is the general relevancy of the information to the receiver, the criticality of the information will normally determine how much effort the receiver will expend to filter it. As a result, the amount of resources devoted to the knowledge appreciation will likely be affected by the commitment of the organization to building a sustainable and effective knowledge base. Where the issues are critical, one can expect an important level of effort in ensuring that the decision are based on high quality of information and proper reference frameworks. Conversely, little attention will be given to information artefacts which are perceived to have little impact on the collective future.

Knowledge management is labour intensive and dependant on the quality of available personnel. Individuals in the organization follow different reasoning paths and give attention to different issues or environment factors. This is a result of the separation of expertise in the context of division of work. Some individuals will develop influence and «knowledgeability» because of their capacity to interpret and give collective meaning to elements which appear otherwise as triviality. As people look up to those which carry the solutions, influence is derived from expertise (Bennis, 1993). More than information, knowledge is a source of leadership and can be transformed into power.

It is claer that the development of an effective Knowledge Management Framework in an organization is as much as technical than a human issue. Believing that the rules and techniques can be a set of algorythms , converted into a system and outsourced to an IT outfit may is either visionary thinking or charlatanism, and probably a mix of both.

7. Conclusion: Knowledge Management Remains Human

One of the conclusions that can be drawn from this discussion

is that the filtering process will continue to require a human

intervention (at least for the time being). This requirement stems

from the obligation to make a series of decisions to determine

the relevance and create added value to the knowledge artefact.

When the knowledge artefact is introduced in the organization,

it is a simple piece of information created or gathered in the

business environment. Its added value is generated by a process

which establishes relevance and builds an interpretation in the

business context. Without this transaction the artefacts lacks

common meaning and is therefore of little interest to the organization.

Through a proper screening process, most organizations actually

build up a knowledge base which, when combined with local knowledge

production, will provide the competitive edge. It is our experience

that this kind of result is not achieved by accident. It requires

the organizational will to invest specialized resources to create

the centres of expertise or knowledge centres to discipline the

process and focus on practical results. Some may propose that

the key is the use of knowledge managers, other will propose the

use of a knowledge management practice and finally some will try

to peddle their ware as the magic bullet.

The weakness of many knowledge management approaches is that they

revive the myths of the omnipotent management information system.

Not that the use of collaboration software and EMail communication

is not a powerful support to knowledge management activities,

but essentially because they remain a supportive mechanism. One

of the driving force behind the information technology is the

quest for the biggest and most integrated data repositories. Such

results can only be achieved though a separation of the information

from its purpose: purposeful productive use. The limit to data

warehousing is its paradigm : standardization of purpose.

Despite what is being proposed by a part of the IT industry, the

transformation of information into knowledge is not a higher form

of data processing. In the business context, it remains an appreciative

process and lack much of the rigour required to develop systematization

and automation through simple business rules. On the other hand,

within any performing organization, it tends to follow a systemic

model where the relevance of pieces of knowledge are given a purpose

and a function within the operational environment.

The mere fact that it is a complex human-based process does not mean that it is not systemic, it should be an indication that the current information technology may not be the proper paradigm for implementing knowledge management.

8. References

Brooking, A., Intellectual Capital, Thompson Press, London, 1996

Phaneuf, J., Godbout, A.J., Beltzner K., and Fortin, R., Knowledge Management Framework, Working Group On Knowledge Management, Godbout Martin Godbout & associates, Technical Report, 1996

Holsapple, C.W. and Joshi, K.D., In Search Of A Descriptive Framework For Knowledge Management, KIKM Research Paper No 118, Kentucky University, March 1998

Lehrer, K., Theory Of Knowledge, Westview Press, San Francisco, 1990

Plotkin, H. The Nature Of Knowledge, Allen Press-Penguin, London, 1994

Kress, G., Turning Information Into Knowledge, IM Magazine, March-April 1993

Troelsch, E., The Social Teaching Of The Christian Churches, English Translation By O. Wyon, MacMillan, New York, 1931

Polanyi, M., Personal Knowledge: Towards A Post-Critical Philosophy, New York, Harper, 1962

Bennis, W., Learning Some Basic Truisms About Leadership, Ray, Michael (Ed), The New Paradigm In Business, Perigee, Los Angeles, 1993

Alain J. Godbout Adm.A. CMC, is Managing Partner, Godbout Martin Godbout & associates, and is a seasoned management consultant specializing in information resources and knowledge management. During his career he has been instrumental in helping Canadian and European public and private sector organizations build sound knowledge management practices. Alain is also a lecturer at University du Quebec in Hull, and he can be reached at Email: godbout@magi.com