Journal

of Knowledge Management Practice, Vol. 9, No. 4, December 2008

A

Case Study Of Successful Implementation Of A Learning

Model

Moria Levy, ROM Knowledgeware

ABSTRACT:

The 21st Century is the century of knowledge and knowledge workers. Knowledge turns to be one of the most important assets of every organization and continual creation of new professional knowledge is a key success factor for innovation and business success. In most organizations, however, new knowledge is created mainly in R&D departments, and not across the organization where current experiences exist. This article describes a successful implementation of a learning model, aimed to build the doctrine of professional practicable knowledge, and based on experience. The article brings a detailed case study, implementing the above, but was used at least in four other cases as a complete model, and partly in many more cases. The model described is unique, yet is based on many of the classic knowledge management and learning models. This paper's value is in its practical, easy and fast process-learning model, which can be used in any organization that wishes to learn from experience.

Keywords: Knowledge creation,

Learning, Experience, Knowledge management, Social services, Case study

1. Introduction

Today’s typical worker is a knowledge worker. This worker might have learned the basics of the job in some formal courses or at university, but most of the practical knowledge derives from hands-on experience. Learning researchers emphasize the importance of learning from experience as part of the learning process. Cell (1984; Preface viii) explains the difference between academic learning and experiential learning:

What, then, of experiential versus academic

sources of personal change? Morris Keeton and Pamela Tate define experiential

learning as: learning in which the learner is directly in touch with the

realities being studied. It is contrasted with learning in which the learner

only reads about, hears about, talks about, or writes about these realities but

never comes in contact with them as part of the learning process.

Kolb (1984) explains that learning from experience is founded on four complementary components: Concrete experience; Active experimentation; Abstract Conceptualization and Reflective Observation.

In many real cases we possess much concrete, particular experience, yet lack the understanding of the big picture. We have difficulties in the abstract conceptualization phase, and therefore our understanding and knowledge are partial. In these cases, we feel as if we work by intuition or "gut feeling." Various people performing the same job have their own unique way of making decisions; knowledge sharing, therefore, is not trivial.

A learning group of the Israeli Fostering Care Services, which participated in the knowledge and learning activities of the Israeli Ministry of Social Services, experienced this challenge. The group was confused about where to start the learning process. A model of prioritization, based on a refined version of the "river" model described by Collison and Parcell (2001), was used: In the first stage, each member of the learning group was asked to write down the five most important topics s/he wished to learn. The group shared their topics, and a unified list containing twenty-one topics was constructed, The list is displayed in its raw format, without any refinement. (The list was refined only later, after the group experienced learning):

¨ Precise diagnosis of a child.

¨ Precise diagnosis of a potential fostering family.

¨ Understanding fostering (including reading between the lines); Integration of several diagnosis reports.

¨ Infrastructure of clear and explicit procedures - clear policy, understanding of the law and official authorizations.

¨ Managing exceptional events facing the community.

¨ Working with professional partners; handling the stress of the job.

¨ Using theory in the field; knowing how to explain the rational of decisions taken.

¨ Learning communication patterns and processes among children.

¨ Updated knowledge in fostering as a routine and in partnership with the academy.

¨ Understanding the process of treatment of children by social services’ municipal offices.

¨ Defining the correct borders between field associations and supervision.

¨ Defining communication programs between the professional partners.

¨ Creative thinking in fostering processes.

¨ Negotiation of a child's needs.

¨ Leveraging the fostering beyond the scope of the professionals and families.

¨ Pairing potential fostering parents with children in need.

¨ The ability to utilize a fostering process.

¨ Time management.

¨ Identifying signals (signaling a potential problem in a fostering settlement).

¨ Managing emergency scenarios.

¨ Managing the communication with the biological parents, guided by the child's needs.

In the second stage, participants were requested to prioritize two topics in which they are knowledgeable and two topics in which they lack knowledge and attribute importance to learning and developing knowledge. Numbers were then added up, requiring prioritization. People had to analyze and understand where they felt the lack of knowledge and, furthermore, the impact of this lack on their work.

Four types of rows were classified:

Low existence-Low request: No Knowledge Management Required.

High existence-High request: No Knowledge Management Required.

High existence- High request: Knowledge Sharing Recommended.

Low existence-High request: Knowledge Creation Recommended.

(existence = high level of knowledge; request = lack of knowledge.)

These lists were later reworked, merging topics and eliminating others (for example, as to management decision, time management was dropped from the list, as the scope was professional knowledge).

|

Subject |

Existence of Knowledge |

Request for Knowledge |

|

a. |

1 |

0 |

|

b. |

0 |

5 |

|

c. |

0 |

1 |

|

d. |

2 |

3 |

|

e. |

3 |

2 |

|

f.

|

1 |

1 |

|

g. |

4 |

1 |

|

h. |

1 |

1 |

|

i.

|

0 |

2 |

|

j.

|

2 |

0 |

|

k. |

5 |

2 |

|

l.

|

0 |

0 |

|

m. |

3 |

0 |

|

n. |

0 |

1 |

|

o. |

1 |

1 |

|

p. |

3 |

3 |

|

q. |

1 |

1 |

|

r.

|

3 |

4 |

|

s. |

0 |

4 |

|

t.

|

3 |

1 |

|

u. |

1 |

2 |

|

v. |

0 |

0 |

The workshop resulted in recommending two initial subjects in which knowledge creation was defined as a critical need. No member of the group regarded himself as professional in these subjects (which would have enabled knowledge sharing): a) Identifying signals (item s). b) Fostering matching (generalization of item b).

A quick study examined whether the knowledge exists outside of the learning group, in the Social Services Ministry, in related professions or on the internet. As almost no external practicable knowledge was found, concepts had to be built and knowledge created.

This article describes the learning model used to create the organizational knowledge. These processes of knowledge creation were characterized by the presence of both concrete experience and active experimentation. The social workers performed these tasks on a daily basis, looking for signals every time they met the fostering family or the child. They experienced settlements that did not succeed and identified signals in certain settlements. In some cases, they saved the settlement, while in others they could not. In all cases, they felt a critical lack of knowledge. The same can be said for the fostering matching process. New settlements were made, each as result of a specific match. The doctrine, however, was missing; the knowledge was in details rather than conceptualized.

During

Since then, the same methodology was reused, building new additional professional doctrines, both for this group, and for other ones. The methodology seems to be stable, and serves as a rapid, effective way for developing new professional knowledge.

Nonaka and Takauchi in their book The Knowledge Creating Company (1995) define four phases in the knowledge creation process: Socialization, Externalization, Combination and Internalization:

Socialization - a process of sharing experiences and thereby creating tacit knowledge, such as shared mental models and technical skills.

Externalization - a process of articulating tacit knowledge into explicit concepts.

Combination - a process of systemizing concepts into a knowledge system.

Internalization- a process, closely related to "learning by doing," of embodying knowledge into tacit knowledge.

The model defined by these researchers deals with how Japanese companies create the dynamics of innovation. This model, enabling the creation of new products through innovation, did not fit the fostering care needs as is. The rational is simple: We often do not want to develop a new product or service, preferring to build upon concepts by which we should work. This is a different type of knowledge creation that is not innovative, but, developed from existing, concrete experiences.

2. New Model

The Nonaka and Takauchi model was not abandoned. Its phases guided us in building an altered model for knowledge development, aimed at implementing knowledge creation with this learning group in the Fostering Care Services. An augmented model was developed to solve the challenge of existing concrete experience with the lack of an abstract conceptual model. The new model, which was the foundation for knowledge creation, includes all four of Nonaka and Takauchi’s phases, but is tailored to fit the situation of doctrine and concept knowledge creation, based on experiences and concrete existing knowledge. The new model developed contains seven steps, including within Nonaka and Takauchi’s components of socialization, externalization, combination and internalization.

The model can be described using the flow diagram shown in Figure: 1:

Figure 1: New Model

2.1. Opening Minds

It is very difficult to start learning; every new creation is challenging. People find it easier to comment on an existing concept than to make the first move, write the first sentences or build the first building block. This first step is critical. Too many learning groups initiated this step but could not progress further. The following tactic was used to overcome this obstacle: Two group members were asked to share with the group a story or case study relevant to the subject to be learned. One was guided in preparing a successful story (even though every success has some faults on the way); the other was requested to speak about a failure (even though some success elements were included as part of the story). The group listened to the stories and questioned their tellers about the processes shared. Some initial, yet unstructured, analysis was initiated. Discussing the subject had several results. People, who were not close enough, became aware; other people were reminded of their experiences and some began sharing these with the group. Unconscious became conscious. People opened their minds. They were "in" and learning could start. This step may take up to two hours.

2.2. Existing Knowledge

The second step deals with structurally collecting the existing knowledge. This phase can take place on the same day as the first step, for both cases described (Signals learning and Optimal Fostering Match learning). The participants had experiences, but no structured knowledge; they were ready to continue. (In cases where this phase takes place at a different time and place, the experiences should be recalled, helping the people prepare for the next phase). Step two aims to begin gathering and organizing existing knowledge, never starting from scratch. It is crucial to leverage the existing known knowledge before starting to create new knowledge. The general subject (not specific experiences) was discussed and the group was asked to define the main building blocks important for the understanding and analysis of the subject. In the case of identifying signals, the group agreed that five different components should to be taken into consideration:

1. The signals (the fostering family’s complaints about money or violence of the child, etc.)

2. Baseline: The child’s starting point at the initialization of the fostering settlement. (Violence of the child in the first place is to be regarded differently than what we are used to).

3. The context (environment) in which the fostering settlement takes place (norms of community in which the child is now living).

4. Level of signals (i.e. how frequently do the signals occur?).

5. Risk factors threatening the fostering settlement and predicting problems (i.e. death in the biological family).

In the learning process of optimal fostering matching, a different list was suggested.

The combination of the five components is the foundation for understanding situations in which the fostering settlement is at risk of collapse. In these cases of knowledge development, materials regarding some of the components could be found in the literature, albeit in a different context (i.e. youth at risk in situations other than fostering). Fostering articles regarding case studies or only partial components’ analysis were found. In advance, one of the learning colleagues scanned existing knowledgebases (closed social working knowledgebases and Internet sources) and relevant articles were gathered. Every article was printed out in at least two copies.

At this point, the group’s twelve members were split into four small teams. The teams were asked to read the articles in advance. Each article was connected to the subject to be learned, and was distributed to at least two teams (overlap is deliberate). Each team was requested, based both on the articles and on their concrete, existing experience, to analyze the suggested components discussed above and write down what they know and the importance of each. The learning group shared the knowledge learned in the teams.

Splitting the group into small teams was essential to the process of effective learning. In large groups, not all the members speak up, but when groups are split into teams of three to four people, all members have a fair chance of raising their experiences and speaking up. Additionally, having more groups enables overlapping of ideas from different perspectives, as people have different views and interpretations. This step may last from two hours to two days.

2.3. Model Definition

The next step is the heart of the concept abstraction. Having discussed the components in teams, the group is ready for abstraction. The components are re-analyzed; some are merged, some split, and others deleted or added. As in innovation processes, the target is to focus on the most significant components and eliminate the exceptions. This process of focusing on the most important elements, based on Kim & Mouborgne's "Blue Ocean Strategy" (2005), is well known. All components are to be integrated into a model, represented as a diagram. The person who guides the learning process will usually be more dominant in this step. Even if all components are in line, their integration into a model, a graphical representation, is not simple, and not everyone knows how to perform such a task. Agreement of all members that the model indeed represents the understanding of the subject is important, and the group may return to the model in further steps and validate or even refine it. Below are two examples of the models built within the learning group for the two subjects for which professional knowledge was created:

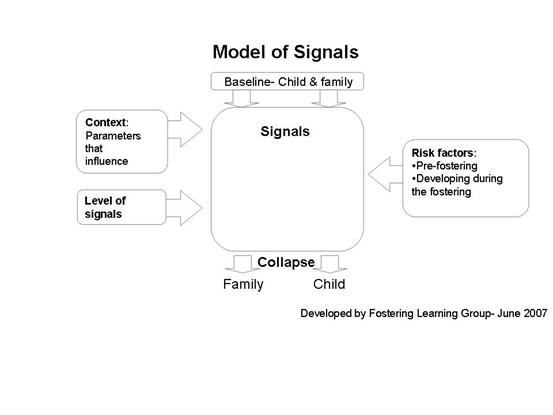

Figure 2: Model Example 1

Explanation: Signals are warnings that may predict a collapse

situation, either of the fostering family or of the child. Signals, however, do

not represent the full understanding of looming collapse. Signals are

influenced by risk factors and must be compared to the known behavior of the

child and family (baseline). Indeed, they cannot be interpretated

correctly without being placed into the right context and having their level

and frequency analyzed. All these components (level, baseline, etc.) influence

signals and help in understanding whether collapse is pending and special intervention

should take place.

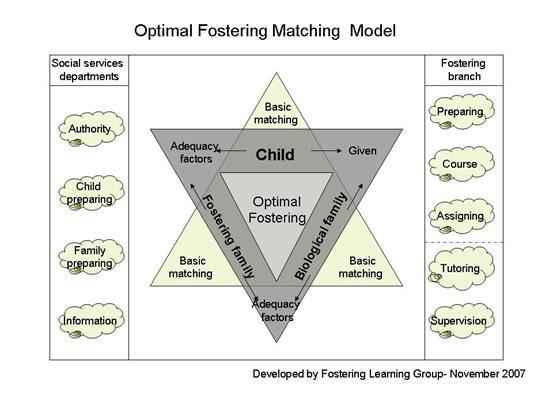

Figure 3: Model Example 2

Explanation: This model deals with optimal fostering matching. Fostering involves three partners: the child, his/her biological family and the fostering family. Each has a basic level of matching. For example, a child who sexually abused others will have a lower level; a fostering family where parents have more free time will have a higher level, etc. The basic matching is never a "yes" or "no," rather a level that, if low, should receive relative compensation. The matching between the pairs is also very significant in finding the optimal fostering settlement. Of course, the pairing of the child and his biological family is a given and therefore not in question. There are, however, important adequacy factors regarding the pairing of the fostering family with the child (e.g. ambition for excellence) and the pairing of the fostering family with the biological family (e.g. spoken languages at home). Only in rare situations will all parameters match. Optimal matching, however, has to take place, and the professional authorities (social services departments and the fostering branch) must focus on enabling a better settlement. This matching is done before the settlement takes place (course, biological family preparation, etc.) and during the fostering itself (through the treatment program and supervision).

2.4. Detailed Knowledge

After agreeing upon the model, the relevant knowledge is documented for each of the components included within. Again, this is conducted in teams of two members each because:

¨ The learning is group-based; it is, therefore, incorrect to assign one person to the task. As many people as possible must take part in this task externalizing the knowledge developed.

¨ Working in big teams is not appropriate for a documentation task.

Furthermore, people find it difficult to document. Therefore:

¨ Working with someone eases the task.

¨ It is less threatening to document a well-defined limited-size piece of knowledge (only one component, half a page to a page).

Each team presents the documented knowledge to the whole group, and a discussion takes place on the written material and on decisions made by the teams while writing. Each team refines the section written to reflect insights added by the group.

2.5. Article

The fifth step deals with integrating all knowledge into one unified article. This article is the new theory, the newly created professional knowledge. When the various pieces are integrated, some editing has to be done, either by the guide or by someone else appointed. This step is necessary, as copying and pasting different writing styles into one article can produce an unreadable piece. Writing is still not complete after this integration: At this point, the knowledge is shared with larger groups of people that can comment and help refine the newly created knowledge. In the case of the Foster Care Services, the article was uploaded to a website, a community practice of Foster Care Services, and all social workers at that branch were asked to join the learning process. The learning group read all their comments and decided whether, where and how to refer to the comments and change the article accordingly.

There are two main benefits in this process of sharing the article with larger groups and enabling comments:

¨ The knowledge developed is crystallized, as more experiences are considered and more people contribute their knowledge and validation.

¨ Assimilation of knowledge takes place. If people are asked to comment and their knowledge is reflected in the newly developed article, they feel involved in the process, and will later more easily accept working accordingly.

2.6.

Tools

This step takes the conceptual abstract constructed and breaks it down back into practical tools. The tools are aimed for the use of specifically defined populations, whether parents, teachers, foster care workers or social workers in the social service departments. Each tool facilitates the use of the defined and structured knowledge in daily life situations. Leaving the knowledge in article format makes it difficult for people who were not part of the learning group to assimilate the knowledge and enjoy the benefits of the learning. Leaving the knowledge in article format also makes it harder for those who were part of the learning to remember everything learned, as not all the knowledge will be implemented immediately. In the case studies discussed, several tools were built.

The tools built as part of the Signal Model include:

¨ Baseline questionnaire - completed mainly by social service departments when the child is accepted for fostering. The questionnaire includes basic parameters important for many needs: optimal matching, understanding of signals and operational guidelines (i.e. medicine the child is allergic to, etc.).

¨ Tracking table - A table containing all signals, according to topic. Every month, the fostering social workers meeting the child mark the columns, according to the child's behavior and general situation, with a signifying color. Each row stands for one signal; thus, social workers identify signals as they occur in an easy manner.

¨ Signal Checklist for families - A list of signals, accompanied by explanations, aimed at assisting the fostering parents to identify signals of the child as they occur.

¨ Short signal checklist for schools- A letter provided for teachers of classes that include children in fostering settlements. The letter includes basic signals, to be viewed in class, and a request for notification when these signals occur.

In the second learning subject, The Optimal Fostering Match, tools are now in preparation. As can be noted, the baseline questionnaire was enlarged to serve both needs.

Next, the tools are tested in the field by the members of the learning group and their colleagues and then refined according to the results of this testing. The built tools are also uploaded to the community practice website, where other people can comment. The learning group, which has the final word regarding the acceptance of changes, discusses all suggestions. Some of the adopted changes also influence the article, or in some cases, trigger the refining of the model. It is easier to justify the concept by testing the practical tools in the field than by reviewing the article written on paper. This step, however, is very sensitive, twofold:

One of the main dilemmas when building tools is the amount of detail to include. Requesting additional reading or more details provides better coverage of the topic and enables better utilization of the learned material. On the other hand, requesting additional reading or more details proves a burden to those who have to re-read or re-fill the form regularly, and thus may yield the opposite situation of no use at all.

Processes are never carried out in exactly the same way, differing from place to place. Tools, defined in a specific way, are naturally easier to adopt in some of the places, which are more controlled or at least have existing processes that are close to those suggested. When commenting, different groups try to bring the tools closer to their world, as they understand these tools will be obligatory and will influence the way each one works on daily routine.

After the first phase of trial and comments, larger circles become involved as part of the routine. The testing step, also referred as a pilot period, lasts from six to eight months.

2.7.

Public Use

The final step transforms the newly created knowledge into public knowledge, to be used all around the organization(s). After the knowledge was twice validated (the article - by comments; the tools - by working with them in the field), it should be shared with larger groups and become part of the organizational knowledge. In the Foster Care Services Learning Group, this meant adding the work with the tools to the work procedures, turning them into obligatory guidelines. In other places, of course, the formalization may be irrelevant and other levels of public use may be applied. The final step is very important, because if the knowledge is created but not widely utilized by all those who could use it as part of their job, there is no point in creating it in the first place. Von-Krogh, Ichijo & Nonaka in their analysis of enabling of knowledge creation (2000) count five enablers of knowledge creation. The last of them is globalization of local knowledge. This is the essence of the last step: making the created knowledge global. Of course, this conclusion is already the start of a new cycle. Routine usage of the knowledge yields newer knowledge through interpretations (see Nonaka and Takeuchi, The Knowledge Creating Company).

3. Analysis Of The Model

The above reviewed Learning Model describes a case study, in which the model was studied and used. This learning method is not revolutionary; it is based on many well-known learning models and adapts the foundations of their ideas. This learning model focuses on the task of building the knowledge outside in - from the field and its concrete knowledge up into the organization (see also Mazvenski & Athanassiou, 2007). The need for such a model derives from the lack of a practical, rapid, effective way for organizational professional knowledge creation. Yet, any new model must be based on classic learning foundations, and the model described above must follow known concepts:

Nonaka and Takauchi (1995) define 4 phases in the process of knowledge creation: Socialization, Externalization, Combination and Internalization; as described above.

Socialization is emphasized in steps 1-4; Externalization in steps 3-6; Combination in step 6 and internalization in steps 6-7 (people work with the tools representing the newly created knowledge, building their new interpretations and new tacit concrete knowledge).

The model also reflects the five knowledge-creating steps defined by Nonaka and Takauchi (1995) and Von-Krogh, Ichijo & Nonaka, (2000):

(1) Sharing tacit knowledge - Team members meeting to share their knowledge of a given product data; individuals share their personal beliefs about a situation with other team members.

(2) Creating a concept - A micro-community attempts to externalize its knowledge, making its tacit knowledge explicit. To externalize knowledge entails expressing shared practices and judgments through language. A concept captures the blend of experience and imagination.

(3) Concept justification - Evaluation of a created concept.

(4) Building a prototype - The prototype is a tangible form of the concept, and it is achieved by combining existing concepts, products, components and procedures with the new concept.

(5) Cross-leveling knowledge - The knowledge is passed to pilot stakeholders and the prototype will be further refined. The prototype therefore becomes a source of inspiration across organizational hierarchies.

Sharing tacit knowledge is the core

of steps 1, 2, 4. Creating a concept is achieved in step 3; the concept is

justified in steps 4, 5,

All three skills defined by Cell (1984) as necessary for learning from experience are included:

¨ Generalization - We seek recurrent patterns in our experience.

¨ Selection - Of all the things to which we could give our attention at any given moment, we select a few upon which to focus.

¨ Interpretation- We see connections between things, pulling them together into a meaningful pattern, and we assess their value or lack thereof for us.

¨ Generalization is included in steps 2, 3, 6; Selection in steps 4, 5; and Interpretation in steps 4, 6.

Kolb (1984) discusses the balance between the four complementary styles of learning: Concrete experience; Abstract conceptualization; Active Experimentation; and Reflective observation.

Concrete experience - Fully open involvement, without bias, in new experiences.

Abstract conceptualization - Creating concepts that integrate observations into logically sound theories.

Active experimentation - Using theories to make decisions and solve problems.

Reflective observation - Reflecting on and observing experiences from multiple perspectives.

In this learning model, it has been shown that creating new professional knowledge may often start (as in Lessons Learned) not with no-knowledge, but rather with concrete knowledge. The Concrete experience is emphasized in steps 1, 2; The Abstract conceptualization in step 3; The Reflective observation in steps 2, 4, 5; and the Active Experimentation in step 6.

The analysis can be summarized in the following table:

|

Step / Compare |

1 Opening minds |

2 Existing

knowledge |

3 Model definition |

4 Detailed

knowledge |

5 Article |

6 Tools |

7 Public Use |

|

Nonaka, Takauchi (phases) |

Socialization |

Socialization |

Socialization Externalization |

Socialization Externalization |

Externalization |

Externalization Combination Internalization |

Internalization |

|

Nonaka, Takauchi (steps) |

Sharing

tacit |

Sharing

tacit |

Creating

concept |

Sharing

tacit Justify

concept |

Justify

concept |

Justify

concept Prototype |

Knowledge

cross level |

|

Cell (Skills) |

|

Generalization |

Generalization |

Selection Interpretation |

Selection |

Generalization Interpretation |

|

|

Kolb (types) |

Concrete

|

Concrete

Reflective |

Abstract

conceptualization |

Reflective |

Reflective |

Active

experimentation |

|

Table 1: Analysis Summary

4. Conclusion

A learning model has been described for creating new professional practicable knowledge. The model is specific for learning from experience and is based on existing, well-known learning models.

The need for such a model derives from the lack of a practical, rapid, effective way for organizational professional knowledge creation. Yet, any new model must be based on classic learning foundations, and the defined model above must follow known concepts.

The learning model described was used in five case studies during 2007-

The model described has successfully facilitated consolidation of individual field experiences and lessons learned there into an organizational knowledge pool. Based on this successful experience, the learning model may be used for many groups and organizations with similar needs.

5. References

Cell, E. (1984), Learning to Learn from Experience,

Collison, C. & Parcell

G. (2001), Learning to Fly: Practical Lessons from One of the World’s

Leading Knowledge Companies, Capstone Publishing Limited,

Kim, W.C & Mauborgne, R. (2005),

Kolb, D. (1984), Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning

and Development, Prentice-Hall,

Maznevski, M.

& Athanassiou, N. (2007), “Bringing

the outside in: Learning and Knowledge Management through External

Networks”, in K.

Nonaka, I. & Takeuchi, H. (1995), The Knowledge Creating Company,

Von Krogh, G., Ichijo, K. & Nonaka, K. (2000). Enabling Knowledge Creation: How to

Unlock the Mystery of Tacit Knowledge and Release the Power of Innovation,

About the Author

Moria Levy, ROM Knowledgeware,

P.O.B. 1213

Position held: CEO of ROM Knowledgeware, Knowledge Management consulting firm; working on Doctorial research in Bar-Ilan University, Israel (Learning from Lessons and Experiences- a KM perspective).