Epistemological Problems

Concerning Explication Of Tacit Knowledge

Ilkka Virtanen, University of

Tampere , Finland

ABSTRACT:

Many authors in the

contemporary knowledge management literature have highlighted explication of tacit knowledge as one of

the most important functions of modern organizations. However, the theories

stressing the importance of explication of tacit knowledge have to adopt

assumptions from both Polanyi’s theory of knowledge and objectivist theory of

knowledge, in which case the resulting epistemological view often remains

puzzling. We analyzed the epistemological foundations of the idea of

explication of tacit knowledge. We argue that the idea of explication of tacit

knowledge is based on a combination of two different epistemological views that

are shown to be mutually incompatible in certain significant aspects.

Keywords: Epistemology, Explication, Explicit

knowledge, Objectivism, Polanyi, Tacit knowledge

1. Introduction

Tacit knowledge has been

one of the most discussed concepts in area of knowledge management (KM) during

the recent years. Tacit knowledge is usually defined as “knowledge difficult to

articulate” (Nonaka and Takeuchi 1995; Baumard 1999), and is therefore often used to refer to

practical knowledge, such as expertise, know-how and professional intuition

that are rooted to personal experiences. It has been also contrasted with

codified, objective knowledge that is easy to share in words and numbers (Busch

2008).

The main motivation for the

popularity of the concept in the area of management studies is the widely

supported claim that organizations can achieve competitive advantages by using

effectively their unique knowledge (Spender 1996). According to many authors,

individuals’ tacit knowledge is particularly important source of unique and

sustainable knowledge in the organizational context (e.g. Argote

and Ingram 2000; Kikoski and Kikoski

2004). Various authors have remarked that individual’s tacit knowledge might be

of little advantage for the organization if it is not shared among other

members of the organization (e.g. Nonaka and Takeuchi

1995; Kikoski and Kikoski

2004). That is why explication of tacit

knowledge has been particularly discussed topic in the contemporary KM

literature.

The concept of tacit

knowledge is adopted from Polanyi’s theory of knowledge. Polanyi, however, did

not present a condensed definition of the concept, which partly has led to

varying interpretations of his theory. Accordingly, while some authors (e.g. Kikoski and Kikoski 2006;

Sternberg 1999) stress the importance of making tacit knowledge explicit to be

further shared, others (e.g. Tsoukas 2003; Hislop 2005) argue that explication of tacit knowledge is

not possible. These two different views are said to represent two different

epistemological schools, objectivist

epistemology and practice-based

epistemology respectively (Hislop 2005). Thus, the possibility of explication of tacit

knowledge is a significant and widely discussed issue in the contemporary KM

literature.

The core of this problem

goes back to the question concerning the nature of tacit knowledge; what is

tacit knowledge, and what kind of epistemology the concept presupposes in its original sense? These questions are the

key to better assess the possibility of explication of tacit knowledge

independently of scholarly emphases. Although epistemic problems are not the

most central matter of management studies, these questions cannot be completely

bypassed if theories concern knowledge conversions or creation of new

knowledge. However, this seems to be often the case in KM literature dealing

with the concept.

We claim that the

explanation of the nature of tacit knowledge must be based on Polanyi’s

epistemology for three reasons:

I.

There

is generally no disagreement over the origin of the concept. This is a widely

recognized fact that most of the KM theorists also mention.

II.

Polanyi

spent a great deal of his career studying this phenomenon and developing his

epistemology. Therefore, as far as is known, he is the scientist who has

studied the phenomenon most thoroughly.

III.

According

to our understanding, not only the expression providing the definition of the

concept but the entire theoretical context signifies the concept to be defined

(Bunge 1967). Hence, the meaning of a concept in a certain theory is dependent

on the theory itself (Tuomela 1973). Therefore,

separating the concept of tacit knowledge from the rest of Polanyi’s

theoretical framework includes the risk of unintentional conceptual change if

the original theory is not taken into account.

The theories that stress

the importance of making tacit knowledge explicit differ in an epistemological

sense from Polanyi’s theory because Polanyi did not make ontological

distinction between tacit and explicit knowledge equivalent to the distinction

often presented in KM literature (usually claimed to be adopted from Polanyi).

Thus, we address the question, what kind

of epistemological theory is required for a procedure of explication of tacit

knowledge. The theories stressing the importance of making tacit knowledge

explicit generally seem to lack this kind of theoretical considerations.

We claim that the

epistemology that enables the explication of tacit knowledge presumes a

combination of two different kinds of epistemologies that are, however, shown

in this work to be mutually incompatible. In this sense the idea of explication

of tacit knowledge seems to lack theoretical plausibility. Also, the introduction of the concept of tacit knowledge to a different kind

of epistemological environment seem to have led to distortion of the

original meaning of the concept.

2. Related Work

According to Cook and Brown

(1999), the traditional understanding of the nature of knowledge is widely

adopted in the literature concerning organizational knowledge. They call this

view an epistemology of possession

due to its way to treat knowledge as an entity that people can possess; it

highlights objectivity of knowledge and therefore privileges explicit knowledge

over tacit knowledge. However, Cook and Brown remark that there is more

epistemic work being done in something that humans can do than can be accounted

in terms of knowledge that humans possess; knowing is doing. Cook and Brown

call this view an epistemology of

practice. It stresses that knowledge is essentially about human activity,

and furthermore, knowledge is embodied in people. Cook and Brown’s thinking

seems to refer also to subjective aspects of knowing. Therefore, this view

raises new issues from the perspective of knowledge sharing compared to the

epistemology of possession.

Hislop (2005) makes practically the same

distinction between two schools based on different kinds of epistemological

assumptions; objectivist perspective

of knowledge assumes that knowledge is an objective entity possible to be

codified into explicit facts by cognitive processes in the human brain. On the

contrary, practice-based perspective

stresses that knowledge is embedded in practice. This means that knowledge is

not seen as an objective entity that can be separated from people. Instead,

development of knowledge is seen as an ongoing process that involves the whole

body; it is impossible to disembody that kind of knowledge from people into

objective form. In table 1 are presented the epistemological core assumptions

of these schools according to Hislop (2005).

Table 1:

Differences Between Objectivist And

Practice-Based Epistemologies

(Hislop, 2005; Cook And Brown, 1999)

|

Objectivist epistemology |

Practice-based epistemology |

|

Knowledge derived from an intellectual process |

Knowledge is embodied in practice Knowing/doing inseparable |

|

Knowledge is disembodied entity/object |

Knowledge is embodied in people Knowledge is socially constructed |

|

Knowledge is objective facts |

Knowledge is culturally embedded Knowledge is contestable Knowledge is socially constructed |

|

Explicit knowledge (objective) privileged over tacit

knowledge |

Tacit and explicit are inseparable and mutually

constituted |

|

Distinct knowledge categories |

Knowledge is multidimensional |

From the objectivist

perspective sharing of explicit knowledge is a trivial procedure because

explicit knowledge is considered to be objective. Also sharing of tacit

knowledge is seen possible when enriched with the presupposition that tacit

knowledge can be converted to explicit. Instead, practice-based epistemologies

do not generally support the conception of explication of tacit knowledge.

Given that our interest is focused in the idea of explication of tacit

knowledge, in Hislop’s terms our analysis

concentrates particularly on the so-called objectivist view.

Despite that the KM field

is closely related to the philosophical questions concerning the nature of

knowledge, it is obvious that its main interests are not in analysis of the

definition of knowledge but in more practical questions such as utility and

value of knowledge, and knowledge sharing. Thus, theory of knowledge in this

context seems to stress the form in

which knowledge may appear. This perspective is understandable as the main

concern is management of knowledge.

On the other hand, in the

area of philosophical epistemology, validity

and origins of knowledge have been the most fundamental problems since the

times of philosophy of Ancient Greek (Vehkavaara

2000). Therefore, the meaning of the term epistemology

in the context of KM is somewhat looser compared to epistemology as a branch of

philosophy that addresses issues concerning what

knowledge is and what justifies it.

Despite the more pragmatic aims of theories of KM, the traditional

epistemological problems, should not be left uncovered––at least if the

resulting KM models are expected to be theoretically coherent and credible.

3. Different Characterizations Of Knowledge: Traditional, Objectivist And Polanyian Views

Traditionally knowledge has

been defined as justified true belief, which is the classical definition of knowledge (Niiniluoto

1996). However, the traditional view on knowledge is not totally unproblematic.

Gettier (1963) was the first to show that a justified

true belief can be false, suggesting that the classical definition of knowledge

is inadequate. Thus, there is no generally accepted consensus about the

definition of knowledge. Nevertheless, the classical definition of knowledge is

often some kind of basis or at least an important point of reference for any

epistemological considerations. Therefore we briefly discuss what the

traditional view consists of, and what kind of properties it requires of

knowledge.

According to the classical

definition, knowing something posits that the thing being known must be

believed. In this sense belief is the basic component of knowledge to which the

truth and the justification conditions are set (Scheffler

1965). To believe something is mentally to represent it as true (Graham 1998).

Hence, belief is a mental state in which a subject holds a proposition to be

true. To represent something mentally as true naturally includes an idea that

the knowing subject is conscious of that

belief (Vehkavaara 2000).

The content of the belief

must correspond the prevailing state of things in

reality in order to be regarded as knowledge; it is intuitively clear that a

false proposition cannot be known (Steup 2008). However, the truthfulness does not make the

belief knowledge according to the classical view. For example, in the case of a

lucky guess it does not seem reasonable to claim that the subject knew how the things were because the

subject had no rational explanation for the belief. In this sense it have to be assessed, what the grounds are for holding the belief. Therefore, a theory of

knowledge is most basically a theory about epistemic justification because

justification makes a belief “epistemically permissible”

(Pollock and Cruz 1999).

According to Vehkavaara (2000) the condition of justification

presupposes that knowledge can be expressed in a form of propositional

sentence(s), because an essential idea behind the condition of justification is

that the “verification” of knowledge should be repeatable, or at least

examinable, by anyone. Indeed, justifiability of knowledge is specifically

related to the ability to publicly present evidence supporting a claim (Niiniluoto 1996). Thus, knowledge is supposed to be presentable linguistically. Also, the

propositional form of knowledge suggests that no knowing subject is actually

required, because a justified, true proposition exists as an ideal object

independent of the knower and time (Vehkavaara 2000).

In this sense the condition of justification seems to have a close connection

with objectivity.

3.1. Objective Knowledge And

Objectivism

As explained earlier, the

theories that highlight the importance of explication of tacit knowledge are

related to objectivist-based epistemological tradition (Hislop

2005; Cook and Brown 1999). Objectivism

can be understood as an ontology or an epistemology.

Objectivist ontology (metaphysical objectivism) refers to the idea that there

is one objective reality that exists independently of human mind (Niiniluoto 1999). We can perceive the existing reality with

our senses, but the understanding we form about the world might not be entirely

correct. Thus, objectivist ontology concerns the world and its form of

existence. Instead, objectivist epistemology holds that our knowledge

concerning the world is objective.

Objectivism as a branch of

epistemology has a history starting from late 1950’s. It refers to Ayn Rand’s philosophical view that a knowing subject can

acquire objective knowledge of reality only through reason. Objective knowledge

can be formed from a perception in a process of concept formation and reasoning

(Darity 2007).

Consequently,

epistemological objectivism essentially concentrates on the objective nature of

reality and on the justification of knowledge. It seems even useless to deal

with the question of the relationship between tacit and explicit knowledge from

the perspective objectivist thinking because, strictly speaking, the notion of

inarticulate and vague (tacit) knowledge is senseless within the objectivist

theory of knowledge; the theoretical framework of objectivism simply does not

support such a conception.

In the next subsection we

present the core of Polanyi’s theory of knowledge. It is precisely the

requirement of justification that differentiates Polanyi’s thinking from the

traditional view.

3.2. The Core Of

Polanyi’s Epistemology

According to Polanyi (1958)

epistemological theories of the time had described human knowledge too narrowly

because an absolute objectivity was traditionally emphasized as an attainable ideal

for knowledge. He claimed that modern science that was based on disjunction of

objective and subjective aimed to eliminate passionate and personal human

appraisals of theories from science. Polanyi claimed that if all the knowledge

were objective, it would be impossible to make scientific discoveries. Instead,

scientific discoveries were often made on the basis of unexplained informed

guesses, intuitions and imaginative ideas that reflected some kind of tacit knowledge. From this critique of

modern epistemology and philosophy of science raised the concept of personal knowledge. According to

Polanyi, all the acts of conscious mind included a personal coefficient; “Into every act of knowing there enters a

passionate contribution of the person knowing what is being known, and … this

coefficient is no mere imperfection but a vital component of his knowledge.”

(Polanyi 1958 p. viii)

Consequently, Polanyi adds

subjective elements of knowing to the traditional conception of knowledge; the

knower is situated in the most fundamental position instead of what is being

known. The knower does not simply pick up the meaning of knowledge but actively

forms it by integrating his personal appraisals to the thing that is being

known. This is exactly opposite approach to epistemological objectivism, which

claims that knowledge should be independent of the knower. However, Polanyi’s

theory is not subjectivist. Polanyi’s concept of personal knowledge has

strongly objective element because it affirms the possibility to establish

contact with knower-independent reality (Mitchell 2006). Thus, in the

ontological sense Polanyi’s theory refers to realism.

3.3. The Structure Of

Knowing: Subsidiary And Focal Awareness

The major feature of

Polanyi’s theory is a distinction between two kinds of awareness that are

involved in all conscious acts. Focal awareness concerns the object of

conscious act represented in the mind, for example a perception of an external

object or a propositional belief. Subsidiary

awareness refers to the basis on which the focal awareness operates.

Processes of subsidiary awareness provide the elements that the focal object

consists of. For example, when we perform a skill, we attend focally to its

outcome, while being only subsidiarily aware of the

several moves we coordinate to this effect (Polanyi 1969). The most essential

idea of the theory is that while attending to focal awareness a person dwells in subsidiary awareness that

contains subsidiary elements, or clues, of the focal target. Polanyi (1964 p.

xiii) explains:

When we are relying in our awareness

of something (A)

for attending to something else (B), we are but subsidiarily

aware of A. The thing B, which we are thus focally attending, is the meaning of

A. The focal object B is always identifiable, while things like A, of which we

are subsidiarily aware may

be unidentifiable. The two kinds of awareness are mutually exclusive: when we

switch our attention to something of which we have hitherto been subsidiarily aware, it loses its previous meaning.

This is the structure of

knowing that Polanyi sees valid for all

acts of knowing. The idea is that the thing we are focally aware of as a

result of a conscious act is formed subsidiarily of

tacit elements, which enriches focal knowledge with personal coefficient.

Therefore we base our knowledge of the things we are focally attending to

something more fundamental.

For example, if we observe

a moving object, we see thousands of rapidly changing clues as one, unchanging

object; we are not aware of calculations of changing distances, variations of

light or movements of our eye muscles, but simply the focally attended object

(Polanyi 1968). The resulting visual perception is a matter of focal awareness.

We cannot reach clues, calculations and physiological functions that take place

in the subsidiary awareness enabling our knowledge of the focal object. The

process has only one direction terminating in the focal awareness.

According to Polanyi the

two kinds of awareness are mutually exclusive; we cannot attend to both of the

awareness at the same time. In fact, we cannot attend to what is functioning subsidiarily at all, because the moment we shift our

attention to the subsidiary elements, it becomes focal losing its subsidiary

meaning, and having its own subsidiary basis. Polanyi describes (1968 p. 31)

this in a following way:

… Anything serving as a subsidiary

ceases to do so when focal attention is directed on it. It turns to a different

kind of thing, deprived of the meaning it had in the triad.

Therefore, the meaning of

tacit knowledge cannot be seized on by

definition. For example, we can shift our focal attention to movements of

our eyes (a subsidiary element) while observing a moving object, but it changes

radically our perception; the thing we are now attending to (the movements of

our eyes) is focal and we can understand hardly anything of how it functioned subsidiarily as a part of attending to the moving object.

3.4. Justification Of

Knowledge According To Polanyi

The focal part of knowing

corresponds relatively well to the belief in the traditional definition of

knowledge; the focal representation is the conscious understanding that the

knowing subject forms of the object of knowing, and that the subject might be

able to articulate. However, this focal “belief” is a result of something more

fundamental, not the starting point of the knowledge, as it is in the

traditional definition of knowledge.

As all knowing is based on

tacit elements in Polanyi’s theory, objective knowing is not possible by

definition. However, logical deduction is a process that comes near explicit

knowing in the sense that it is based on connecting focal items, namely the

premises and the consequent (Polanyi 1975). The deductive conclusion is

attained using operations with fixed mental structures, which minimizes the

need of indwelling to subsidiary awareness because the premises are already

given (Polanyi 1965). The most important difference between deduction and

knowing based on tacit subsidiaries is that deduction is a reversible process;

it is possible to go back mechanically from the consequence to the premises.

However, knowing based on tacit subsidiaries is not similarly reversible. It is

not possible to go back from the integrated focus to its subsidiaries (Gill

2000).

Thus, in addition to being

capable of stated clearly, explicitness seems to refer also to the possibility

to trace the origins of the focal knowledge––the justification would make knowledge more explicit.

However, knowledge cannot be exhaustively

justified because it is always based on unspecified particulars (Polanyi

1968). This logic leads to the

culmination of Polanyi’s theory: the rejection of the idea of fully explicit

knowledge.

This claim might seem

problematic because it questions our ability to e.g. to verify scientific

knowledge claims, meaning that knowledge would always be only subjective.

Polanyi (1958) answered this problem by stressing that knowing is a responsible

act that claims for universal validity. As he (Polanyi 1958 p. 65) puts it:

It is the act of commitment in its

full structure that saves personal knowledge from being merely subjective.

Intellectual commitment is a responsible decision, in submission to the

compelling claims of what in good conscience I conceive to be true.

Therefore even scientific

knowledge claims cannot be verified by means of explicit articulation. The

confirmation of scientific knowledge claims would require the use of skills and

insights, which themselves lie outside of empirical demonstration (Gill 2000).

Instead, knowledge will be tested in reality that all knowing agents can

access; knowledge will justify itself in case it is worth it. On the other

hand, reasons that justify our beliefs can be repealed as our understanding of

the subject area accumulates. This, indeed, seems to be often the case in

science.

4. Epistemological

Framework For The Idea Of Explication Of Tacit

Knowledge

The idea of explication and

sharing of tacit knowledge was originally made famous by Nonaka

and Takeuchi (1995) in their theory of organizational knowledge creation. Their

SECI-model describes conversions between tacit and explicit knowledge types.

The most essential part of the model is the conversion of tacit knowledge to

explicit (Nonaka and Takeuchi 1995). Since the

publication of Nonaka and Takeuchi’s theory tens of

authors have embraced the idea of explication of tacit knowledge.

The idea of explication of

tacit knowledge is rooted on the distinction between explicit knowledge and

tacit knowledge (Hislop 2005). E.g. Nonaka and Konno (1996 p. 42) make the point clear by

stating: ”There are two kinds of knowledge: explicit

knowledge and tacit knowledge.” Despite this classification, many authors still

recognize some kind of inseparability between these two types (e.g. Nonaka and Takeuchi 1995; Ambrosini

and Bowman 2001). However, explication of tacit knowledge seems to logically

presume such a classification; the aim, after all, is to convert knowledge

existing in a tacit form to more exploitable explicit form. Generally speaking,

there hardly is any conversion of one form to another form if two or more

different forms are not presupposed.

According to KM theories

embracing the idea of explication of tacit knowledge, explicit knowledge is

seen codified, impersonal and objective (Hislop

2005). As Nonaka and Konno (1998) put it, ”Explicit knowledge can be expressed in words and numbers

and shared in the form of data, scientific formulae, specifications, manuals

and the like.” Thus, explicitness seems to refer to the form in which knowledge

is presented. Also, explicit knowledge is assumed to include the correct

meaning unchangeable and ready to be received by anyone. This characterization

of explicit knowledge clearly sets a strong objective nature to that kind of

knowledge and corresponds well the traditional definition of knowledge.

Tacit knowledge is usually

defined as subjective knowledge that is not

yet explicated, considering tacit knowledge as a latent resource that

needs to be shared (e.g. Sternberg 1999; Nonaka and

Takeuchi 1995; Kikoski and Kikoski

2004). The use of the concept of tacit knowledge in general is very

inconsistent depending on author, but according to the usual characterization

it refers to expertise or know-how that is difficult to articulate.

Hislop (2005) considered the theories

concerning explication of tacit knowledge objectivist opposing them to

practice-based epistemologies. However, this classification of epistemologies

seems somewhat crude in a sense that the idea of vague and non-justified

knowledge cannot be accepted easily into the realm of objectivist thinking, in

which the strict justification is a fundamental requirement for knowledge. For

example, expert’s intuitive hunch simply is not knowledge according to

objectivist definition because it is not based on rational, objective

reasoning. In order to be useful or even understandable a concept must be

supported by other concepts within a conceptual system. This is not the case of

the concept of tacit knowledge within the objectivist framework. However, the

theories concerning explication of tacit knowledge would consider intuition as

an instance of tacit knowledge.

Therefore, the theories stressing the explication of tacit knowledge are not

objectivist. Rather, they seem to be some kind of extensions of traditional

view on knowledge, because according to these theories objective and “real”

(explicit) knowledge can be created basing on non-specific forms of ”knowledge” (tacit

knowledge).

In sum, the theories of

explication of tacit knowledge seem to be based on a relatively straightforward

distinction between tacit and explicit knowledge. The notion of explicit

knowledge comes from traditional view on knowledge, whereas the notion of tacit

knowledge is based on Polanyi’s theory of knowledge. Since there is no explicit

knowledge according to Polanyi’s theory, and unjustified tacit knowledge seems

rather questionable idea from the perspective of traditional theories of

knowledge, explication of tacit knowledge requires an epistemological

environment that combines Polanyian elements with

traditional idea of knowledge.

4.1. Explication Of

Tacit Knowledge Enabling Epistemology

The idea of explication of

tacit knowledge presupposes that the inarticulate tacit knowledge is first made

articulate. An articulated, explicit form of tacit knowledge can then be shared

with other individuals. This idea clearly has a strong objectivist

presupposition; as long as tacit knowledge is explicated, it is supposed to be

understandable and usable by others as such.

Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995) have considered

the definition of knowledge that their theory presupposes. They (p. 58)

explain:

In our theory of organizational

knowledge creation, we adopt the traditional definition of knowledge as ”justified true belief.” It should be noted, however,

that while traditional Western epistemology has focused on ”truthfulness” as

the essential attribute of knowledge, we highlight the nature of knowledge as

”justified belief.”

Nonaka and Takeuchi do not make clear whether

this definition concerns both explicit and tacit type of knowledge. If this is

considered to be a general definition of knowledge, and knowledge is then

supposed to have various types, this implies that the definition concerns both

types of knowledge; both tacit and explicit knowledge are justified beliefs.

However, according to

Polanyi’s theory indefinable tacit elements cannot be rationally justified,

which makes knowledge partly unjustifiable in general. Also, as Vehkavaara (2000) remarks, a requirement of justification

presupposes that the representation of knowledge in question can be made linguistic. However, the most common

feature of definitions of tacit knowledge in the KM literature is the problem

of articulation. Also, intuitive knowing is often equated with tacit knowledge

in KM literature. It is self-explanatory that an intuition is just an intuition

exactly because of the lack of justification; it is a feeling of knowing

something without a well-defined explanation. Therefore the requirement of

justification supposedly cannot concern tacit knowledge in these theories.

Consequently ‘justified

belief’ may only concern ‘explicit knowledge’ in the theories that make the

distinction between different types of knowledge. This seems to place tacit and

explicit knowledge in an unequal position in a way that is contrary to

Polanyi’s thinking; instead of being a fundamental basis of all knowing, tacit

knowledge is seen rather as some kind of possible resource for new, ”real”

knowledge. Now, in the case of explication of tacit knowledge it is logically

presumed that tacit knowledge functions as a justification of explicit

knowledge as it is the only source of this attained knowledge. However, if

tacit knowledge itself is at most very weakly justified, can it function as a

justification of something else?

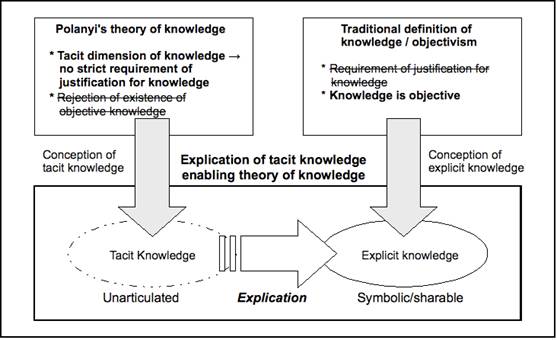

In sum, the idea of

explication of tacit knowledge seems to provide that the attained objective

knowledge is based on a weak justification, that is, for example on

characterizations of beliefs, hunches and implicit know-how. In other words,

the requirement of objectivity of knowledge is seen to true, but the

application of Polanyi’s thinking leads necessarily to rejection of requirement

of rational justification. Hence, the resulting epistemology seems to be a

combination of Polanyian epistemology and the

traditional view on knowledge; it both assumes and rejects some features from

both views. This idea is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1:

A Model Of Explication Of Tacit Knowledge

Enabling Theory Of Knowledge

The

concept of tacit knowledge comes from Polanyi’s theory of knowledge, but the

idea of explicit knowledge corresponds to the traditional,

or even objectivist view, on knowledge. The resulting theory of knowledge has

to reject some features both from Polanyi’s theory of knowledge and from the

traditional view on knowledge (struck through in the upper boxes of the

Figure). The features that the resulting theory of knowledge adopts from these

theories are highlighted in the upper boxes of the Figure. The problems concerning the

combination of these two different types of epistemologies are discussed in the

next section.

5. Problems Of The Explication Of Tacit Knowledge Enabling Epistemology

Given that the basis of

Polanyi’s theory of knowledge was a critique against the objective ideal of

knowledge, it is not surprising that these two views conflict in some crucial

points. This is also why an epistemology that combines features from both of

these theories seems to head for some theoretical problems.

5.1. Non-justified Objective Knowledge

The idea of accepting

non-strict criteria for the basis of objective, explicit knowledge that can be

exchanged between individuals seems to be controversial in itself.

In a theoretical level, to attain reliable objective knowledge it should be

derived and justified by anyone based on the same criteria––this is the basic

idea behind the requirement of justification; people should end up having the

same conclusion, which cannot be generally expected if there are no

recognizable premises or if the premises vary a lot from individual to

individual.

As objectivist epistemology

(and also Polanyi) states, logic and reason are the most straightforward means

to attain fully objective knowledge. Objectivist epistemology considers this

possible, whereas Polanyi rejects the idea of fully explicit knowledge.

However, neither of these epistemologies, nor the traditional view on

knowledge, accepts that objective

knowledge can be based on vague justification.

Let us consider a concrete

example of a theoretical problem that follows from this view. Kikoski and Kikoski (2004 p. 72),

among others, illustrate the difference between tacit and explicit knowledge by

giving characteristics that distinguish tacit knowledge from explicit

knowledge:

Ø Explicit (known): Public,

conscious/aware, logical, certain, strong, hard, structured, goal oriented,

stable, direct perception, rules/methods/facts/proof.

Ø Tacit (not yet known): Private,

unconscious/unaware, alogical, uncertain, fragile,

soft, unstructured, indeterminate, unstable, indirect, subception,

intuition/sensing.

Drawing from Polanyi, Kikoski and Kikoski (2004 p. 73)

state: “all knowledge either is tacit, or is rooted to tacit knowledge; that

is, explicit knowledge depends on and is encompassed by tacit knowledge.”

However, following their characterization of different knowledge types it seems

logically controversial, that strong, certain and stable knowledge is based on

fragile, uncertain and unstable knowledge.

Therefore, tacit knowledge

understood as a foundation of all knowledge (the Polanyian

conception) simply is not compatible with the idea of objective, explicit

knowledge. If the idea of fully objective knowledge is, however, still adhered,

it leads to distortion of the concept of tacit knowledge; its original

intension must be modified in order to make it fit the new theoretical

environment.

5.2. Simplified Image Of

Tacit Knowledge

Polanyi’s notion of tacit

knowing goes far beyond the idea of tacit knowing defined merely as intuition

or context-specific know-how that accumulates as a result of experience.

Instead, tacit knowing belongs inextricably in all conscious acts. The

predominant conception of tacit knowledge in the KM literature that supports

the idea of explication of tacit knowledge seems therefore to be based on

simplification of the concept of tacit knowledge.

Let us consider an example

given by Sternberg (1999 p. 232) as he explains the way explication of tacit

knowledge reduces individual differences:

For example, if, in the past,

knowledge about the importance of buying the boss a gift for his or her

birthday was tacit, those who possessed this knowledge were at distinct

advantage. But if now everyone knows and uses this piece of knowledge, it will

no longer serve to differentiate employees, in the boss’ eyes, and most likely

some other as––yet tacit knowledge will take its place. As this example points

out, tacit knowledge can become explicit.

The awareness of certain

way of action (as in this case) is hardly unspecified or subsidiary. “Tacit

knowledge” in this example, namely the awareness of the importance of buying

the boss a gift, seems to be a focal belief (justified or not) that can be

shared if wanted; someone simply knows

or believes that buying a gift is

important in certain culture. This kind of conception of tacit knowledge has

very little to do with Polanyian contents of

subsidiary awareness. In fact, we might critically ask,

what additional value or explanatory power the introducing of concept of tacit

knowledge brings to this example?

The way intuition and its

relation to tacit knowledge are discussed in the literature of management

studies serves as another example of the simplified conception of tacit knowledge.

Nonaka and Konno (1998 p. 42), among others, argue

that intuitions and hunches fall into the category of tacit knowledge. Also Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995) describe externalization (the

conversion of tacit knowledge to explicit knowledge) by saying that the use of

figurative language is a way to articulate intuitions and insights. From this

seems to follow that articulation of intuition is considered to be articulation

of tacit knowledge, which pretty much equates tacit knowledge with intuition.

However, it is important to make a distinction between the conscious

representation of unexplained feeling of knowing something (simplified view on

tacit knowledge) from the meaningful elements that precede and enable the feeling of knowing (Polanyian

view on tacit knowledge).

The sensation of knowing a

solution (not to speak of its verbal description) belongs in Polanyi’s terms to

the focal, not the tacit, part of that act. Indeed, a relevant question seems

to be, where the sensation of knowing does come from. Why is the intuition just

that and not something else? An intuition must be based on something because

otherwise it would be just a random guess. In Polanyi’s terms integrated

subsidiary knowledge that finally forms the focal sensation remains unexplained

in the process. Thus, intuition is an innate sensibility to coherence that

cannot be explained with rules or algorithms (Polanyi 1966). The knowledge on

which intuition is based remains tacit. As Polanyi (1968 p. 42) puts it:

It is intuition that senses the

presence of hidden resources for solving a problem and which launches the

imagination in its pursuit. And it is intuition that forms there our surmises

and which eventually selects from the material mobilized by the imagination the

relevant pieces of evidence and integrates them into the solution of problem.

Therefore, if intuition

itself is equated with tacit knowledge, we logically need a third level of

knowledge that is even more quintessential than tacit knowledge, namely the

instances of meaning that form the intuition. Although intuition indeed is an

outstanding manifestation of tacit knowing, tacit knowledge does not seem to

become articulated in the process of articulation of the intuition. Instead,

intuition seems to only reflect knower’s tacit resources more or less the same

way that a skilful performance reflects performer’s skills that also cannot be

described in words.

5. Conclusions

Explication of tacit

knowledge has been proclaimed as the most important function of modern

organisations in the contemporary KM literature. However, it seems that the

theoretical grounds of this idea has not been profoundly studied, which cuts

down the plausibility of the theories stressing the importance of making tacit

knowledge explicit. On the other hand, the development of efficient practises

is based on coherent theories. This suggests that the conception of knowledge

still calls for more theoretical development and research also in the

organizational context.

We have described two

significant theoretical problems of the idea of explication of tacit knowledge.

First, the division of knowledge into tacit and explicit.

Interestingly, many authors claim that the classification of knowledge to tacit

and explicit comes from Polanyi’s theory of knowledge (e.g. Baumard

1996; Spender 1996). To be sure, focal (“explicit”) and subsidiary (tacit)

knowledge are central concepts in Polanyi’s epistemology. However, the

distinction is not ontological, but functional. Polanyi did not say that certain

things are known tacitly, while others are known explicitly. Instead, the

distinction describes the structure of knowledge that concerns all acts of knowing being the basis of

Polanyi’s theory of knowledge–it is not a theory of the

existence of two types of knowledge.

Second, theories that

embrace the idea of converting tacit knowledge to explicit are based on two

mutually incompatible epistemologies. The concept of tacit knowledge is

obviously adapted from Polanyi’s theory of knowledge, whereas the characterization

of explicit knowledge corresponds objectivist theory

of knowledge. The most crucial contradictory feature is the view that these

theories take on the requirement of justification. Interestingly, many authors

seem to bypass this controversy. Hence, the focus seems to be on the questions

concerning application of tacit knowledge whereas the considerations concerning

the theory of knowledge that the application of the concept presupposes are

almost completely bypassed.

Polanyi’s theory does not signify

that people could not share knowledge or have same conceptions concerning

reality. Knowledge does not have to be entirely objective for that people could

act efficiently together. The guidance of an expert undoubtedly is an immense

help when a non-professional tries to assimilate a certain skill. Therefore we

do not want to question the methods and goals of the theories of knowledge

creation. However, this does not change the fact that the concept of tacit

knowledge is being used in a questionable, simplified and even incorrect way in

some of the KM literature, which has separated its meaning from its original

role as a foundation of conscious acts, reducing it to refer to any type of

knowledge that is difficult to manage.

Tacit knowledge is first and

foremost a theoretical concept (i.e. a concept introduced by a theory), and

hence, its application even in more practical environment should be based on

the original theory. However, many authors seem to base their conception of

tacit knowledge on the loose idea “knowledge difficult to articulate” that can

refer to virtually any mental or social phenomenon. As the extension of a

concept grows this way, it is in danger to become unclear, even meaningless,

nonsense.

7. Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to

8. References

Ambrosini, V., Bowman, C. (2001), Tacit

Knowledge: Some Suggestions for Operationalization. Journal of Management Studies, 38(6),

811-829.

Baumard, P. (1996), Organizations in the

Fog: An Investigation into the Dynamics of Knowledge. In Moingeon,

B., Edmondson, A. (eds.), Organizational

Learning and Competitive Advantage (pp. 74-91), Sage Publications Ltd,

Baumard, P. (1999), Tacit Knowledge in Organizations, Sage Publications,

Bunge,

M., (1967), Scientific Research I, Springer-Verlag

Berlin, Heidelberg.

Busch, P. (2008), Tacit Knowledge in Organizational Learning,

IGI Publishing, Hershey.

Cook, S., Brown, J. (1999),

Bridging Epistemologies: The Generative Dance Between

Organizational Knowledge and Organizational Knowing. Organization Science, 10(4), 381-400.

Darity, W. (2007), International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences (Second Edition). Macmillan Reference USA,

Gettier, E. (1963), Is Justified True

Belief Knowledge? Analysis, 23, 121-123.

Gill, J. (2000), The Tacit Mode.

Graham, G. (1998), Philosophy of Mind. An

introduction (second edition), Basil Blackwell,

Oxford.

Hislop, D. (2005), Knowledge Management in Organizations. A Critical Introduction, Oxford

University Press Inc,

Kikoski, C., Kikoski,

D. (2004), The Inquiring Organization––Tacit Knowledge,

Conversation, and Knowledge Creation: Skills for 21st-Century

Organizations,

Mitchell,

M. (2006), Michael Polanyi, ISI

Books, Wilmington.

Niiniluoto,

Niiniluoto, I. (1999), Critical scientific realism, Oxford University Press,

Nonaka,

Nonaka I., Takeuchi H. (1995), The Knowledge-Creating Company–How Japanese

Companies Create the Dynamics of Innovation, Oxford University Press, New

York.

Polanyi,

M. (1958), Study of Man,

Polanyi, M. (1964), Personal

Knowledge: Towards a Post-Critical Philosophy (second

edition), Harper and Row,

Polanyi, M. (1965), On the Modern Mind. Encounter, 24, 12-20.

Polanyi, M. (1966), The Tacit Dimension, Doubleday & Company, Garden

City.

Polanyi,

M. (1968), Logic and Psychology. American

Psychologist, 23, 27-43.

Polanyi, M. (1969), Knowing and Being, Routledge

& Kegan Paul,

Polanyi, M. (1975), Meaning (with Prosch,

H.),

Pollock, J., Cruz, J.

(1999), Contemporary Theories of

Knowledge, Rowman and Littlefield Publishers Inc,

Lanham.

Rand, A.

(1962), Introducing Objectivism. Objectivist Newsletter I, 35.

Scheffler, I. (1965), Conditions of knowledge,

Spender, J.C. (1996),

Competitive Advantage from Tacit Knowledge? In Moingeon,

B., Edmondson, A. (eds.). Organizational Learning and Competitive Advantage (pp. 56-73), Sage

Publications Ltd,

Sternberg,

R. (1999), Epilogue––What We Know about Tacit Knowledge? Making the Tacit Become Explicit.

In Sternberg, R., Horvath, J. (eds.). Tacit Knowledge in Professional Practice:

Researcher and Practitioner Perspectives (pp. 231-236),

Steup, M. (2008), The

Analysis of Knowledge. In Zalta, E. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia

of Philosophy (Fall 2008 Edition).

http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2008/entries/knowledge-analysis/. Cited 11 Nov 2009.

Tsoukas, H. (2003), Do We

Really Understand Tacit Knowledge? In Easterby-Smith,

M., Lyles, M. (eds.). Handbook of Organizational Learning and

Knowledge (pp. 410-427), Blackwell, Oxford.

Tuomela, R. (1973), Theoretical Concepts, Springer, Wien.

Vehkavaara, T. (2000), Tietoa Ilman Uskomuksia. (Translated:

Knowledge without Beliefs). Königsberg, 3, 98-111.

About the Author:

Ilkka Virtanen works as a researcher at Department

of Computer Sciences at University of Tampere, Finland.

Ilkka Virtanen, Department of Computer

Sciences, 33014