An Autonomous

Perpetual Mechanism For Collective Knowledge Work

That Redefines

Knowledge Management

Raj Kumar, Director, Aim Knowledge Management Systems Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India

ABSTRACT:

The mechanism to assimilate and apply collective knowledge requires workers to organize their contribution and next action. It dates beyond 300BC. The rapid change underway exceeds its knowing-doing capacity causing wishfulness, politics, knee-jerk reactions, and inertia. The knowledge process serendipity has foiled IT’s attempt to upgrade the mechanism for driving superior judgments and productivity. The incentives essential for motivation trivialize the knowledge work required for sparking insights, spurring innovation and reducing the knowing-doing gap, to “Give” and “Take”. The science of interactions defines repeatable components for normalizing knowledge processes. Teamwork norms harness IT and evolve the mechanism to organize and anticipate worker actions. A tell-all smart interface helps assemble the component flow and work processes on each event. Replication technology enables ubiquitous knowledge work. The mechanism’s seduction for intra/extranet collaboration earns it the sobriquet bmail. Its way fosters perpetual free-flow for purposeful knowledge creation and destruction to advance learning, governance and team-ability.

Introduction – Improving

The Collective’s Power To Deliver Success

Nonaka (1991) set the stage

for superior collective thinking by emphasizing the importance of “tapping

the tacit and often highly subjective insights, intuitions and hunches of individual employees and making

these insights available for testing and use by the company as a whole”. Since

then story telling (Buckman Labs, 2001) to communicate concepts, knowledge

sharing with customers (World Bank, 2001), communities of interest (Cynefin,

2002), internal knowledge sharing (Xerox, 2001), knowledge transfer (Dixon,

2000), Customer Relationship Management and Business Intelligence have been

associated with Knowledge Management (KM) and contributed significantly to

business performance. Organized collective thinking and its application are

included in KM but have yet to assist teams focus in their daily work to make quality

decisions, progress growth, sustain initiative, and reduce the anxiety of stakeholders.

9/11 established its importance (Rabbi Salomon, 2001):

“The tragedy today is not that our lives will never be the same again. The

tragedy is that, in all likelihood, our lives will actually be very much the

same again.”

Business results (Marcum

& Smith, 2003) reflect the tragedy:

“By the time you finish reading this article (999 words),

forty-six businesses will shut down and three will have filed for bankruptcy.

By the end of the day over 2100 will have called it quits….”

It is widely believed that

professionals behave rationally. Sufi philosophy (El-Ghazali, 12 AD, pp. 55)

records a key human frailty: “what

people call belief may often be a state of obsession …. it is essential for

people to be able to identify it”. The Tao Te Ching or “The Virtuous Way

To Ultimate Reality” (Lao Tzu, 500 BC, Part 1) eloquently describes its impact:

“Those who are bound by desire see

only the outward container.” Increase in possibilities during uncertain

times pronounce this weakness of human nature. Indian philosophy defines wisdom

as the ability to pierce Maya or the surrounding illusion. Tom Peters (Peters,

1993) encourages “cannibalization” to

strip away the dross. IBM’s Cynefin Center Of Organizational Complexity

(Snowden, 2000) believes reason lies buried in the complex and chaotic

interactions. An authoritative study of wrong decisions (Marcum & Smith,

2003) has reported:

“Political pressure, or the intensity

of a decision, often prevent people from facing the facts that are crucial to

the company. Our research shows the damaging effects of ego, facades, lazy

thinking, and politics on the businesses top and bottom lines.”

The following anecdote

(Shepherd et al, 2003) illustrates another aspect of the elusive reality:

“A scientist is

searching for dinosaur traces. One long day, while standing in a seemingly

large crater, he vented in frustration, ‘I see no evidence of a dinosaur

anywhere.’ Hearing this his colleague, up in a helicopter, radioed back to

inform he was standing within a huge footprint.”

Knowledge Management then

must enhance the collective’s power to perceive the reality. The way of working

has considerable importance. It determines innovation, the single most

important determinant of business success. While KM pioneer Richard Ballard’s

adage (Ballard, 2000) “The more you

know, the fewer the choices” is true, it is also true that work must

help internalize knowledge for it to be useful, e.g., the fresh graduate is

often confused by learning. IDC’s estimate that the Fortune 500 will loose 31.5

billion dollars in 2003 due to intellectual re-working, sub-standard

performance, and unavailable resources emphasizes the need to manage knowledge

for results. Accountability is essential to overcome the failing (Rabbi

Salomon, 2001): “We forget...we

deny...we rationalize - and sadly, we stay the same”.

The Need For A Superior

Mechanism

The corporate need is sustained

success. Countries need good governance (UNESCAP), i.e., the process of decision-making and the

process by which decisions are implemented (or not implemented).

Developing and applying collective knowledge daily to operations may only be

managed by organization. Both, the country and corporate require a reliable

mechanism that:

¨

Will

support agile teams, promote knowledge absorption and unify team efforts to

apply it

¨

Will

organize purposeful knowledge exchange to spark insights and spur innovation

¨

Will

coordinate distributed action on each event and aid leverage the knowledge of

experts

¨

Will

ensure decisions have every chance to be grounded in reality, strategy,

perspective, etc.

¨

Will

offer a reliable facility for introspection, focus and more quality decisions

in a given time

¨

Will

counter complacency, foster alertness to reality and anchor prudent risk

taking, and

¨

Will

manage accountability, expectations and follow-up on each event to quell

anxiety.

The pursuit of knowledge is

as old as ancient India’s Rig Veda (first verse, ~1200 BC): “Let noble ideas come to us from everywhere”. Chanakya (Naik, 2002), the powerful

minister who master-minded the roll back of Alexander the Great’s invasion of

divided India in approximately 322BC, understood “Knowledge is important. Knowledge is cumulative. Once it exists, it

grows.” The welfare

administration instituted by him ran a huge domain, almost the size of India,

for over a century. He held the king responsible for its motivation, reasoning

that “one wheel alone does not move a chariot”. His parameters of good governance,

viz., organization, focus, thinking ability, character, communication and

vigilance against excess and laziness apply even today. The concept of an

User-conducted mechanism to build a team’s ability to assimilate and apply

knowledge, viz., focus, infer reality, formulate strategy, define problems,

innovate, develop perspective, etc., is thus ancient. The nineteenth century raised the

ability with better logistics enabled by the telegraph (1844), phone (1876),

wireless (1895), and transport revolutions.

The twentieth century

raised the User-conducted mechanism’s team-ability with professional management

and better structures. More possibilities created by rapid

change in technology, attitudes, competition, globalization, etc., have now

swamped the team-ability. Terrorism has raised uncertainty. Of 500 companies surveyed (KPMG

2002/3, insight 4), knowledge was a strategic asset for 80% but they had

difficulty achieving its benefits: 45% did not realize decision-making gains,

while 55% could not improve access to experts. An earlier report (KPMG, 1999,

Item 1.6) reported 65% suffered from information overload and (Item 1.8) only

1% had succeeded in their strategy to assimilate and apply collective knowledge

daily.

Drucker (1999, pp.135) has

set a goal for higher team-ability: “The most important,

and indeed the truly unique, contribution of management in the 20th century was

the fifty-fold increase in the productivity of the manual worker in manufacturing.

The most important contribution management needs to make in the 21st century is

similarly to increase the productivity of knowledge work and the knowledge

worker.” Productivity is not faster decisions but more quality decisions, i.e.,

response to reality with strategy and perspective, etc., in the same time.

The

knowledge mechanism can aspire to put the company in learning mode to be great.

Senge (1990) has described the disciplines an organization needs to pursue to

lead change, e.g., shared vision, team learning, etc. Collins and Porras (1999)

and others have identified the knowledge work and abilities that distinguish

the super achiever companies from the rest, e.g., the pursuit of audacious

goals, countering complacency, sagacious experimentation, etc. After 2300 years of the knowledge

imperative, Knowledge Management then must “bake in”

(Davenport, 1999) a dependable mechanism to develop and apply collective

knowledge for growth and results in times of rapid change with protection from

human frailty in uncertainty.

The Nature Of Collective

Knowledge Work

Conduct of knowledge

processes like problem definition, strategy formulation, etc., determines

team-ability. Knowledge processes also enable organization-learning disciplines

like shared vision, self-mastery, etc., and activities that improve risk taking

for visionary growth like setting audacious goals, reinforcing values, etc.

Teams perform them by doing knowledge work, i.e., establishing working

assumptions and conclusions to be revised as results accumulate, and acting on

them. Members evolve opinion with a purpose defined by the knowledge process.

Collaboration to develop content is an associated activity. Follow-up and

accountability is key to limit excess and mental laziness. The process

effectiveness determines the collective responsibility and hence courage for

the firm action needed to reduce the knowing-doing gap.

The knowing-doing gap

distinguishes knowledge work from collaboration. Collaboration could just be an exchange of information.

Knowledge work takes responsibility for results. It is aided by quiet time and

organization, is rather sensitive to autonomy and is strongly determined by the

work experience (Davenport & Cantrell, 2002). It follows collaboration and

is rather serendipitous:

¨

Knowledge

work normally involves a mix of knowledge processes, e.g., problem definition

followed by solving followed by review of facts and so on at the discretion of

personnel.

¨

Knowledge

work is primarily agreement on the assumptions and conclusions to apply. Work

must be organized and opinions classified, viz., problem, strategy, etc., for

efficient application of knowledge in context by organization members, spread

across departments.

¨

The work may involve a study of related past events, particularly successes and

failures.

¨

The

next knowledge action could be in parallel or sequential, with or without

transfer of accountability, conclusive or circulatory, etc. Personnel thus have

discretion over selection of personnel, process, action and opinion label in

contributing to the knowledge flow.

¨

The

knowledge worker may hold multiple roles across departments and locations. Each

role normally has to deal with multiple events and multiple personnel, and the interactions

multiply daily. The worker has to participate responsibly on each event amidst

chaos.

¨

The

conduct of knowledge work may be asynchronous and anytime and anywhere,

including offline. Besides, it would be inefficient to depend upon the desired

contact/s being available. This requires conflict management on development of

content.

¨

Knowledge

work generates anxiety. Personnel always need to know their accountability

(where they have to take action) and outstanding expectation (where they have

taken action) on work-in-process. They can lower anxiety with a prompt overview

and action like recall or guiding downstream discussion or contributing to the

emerging opinion, etc.

¨

Personnel

need shielding from anxiety over security, deadlines, oversights, follow-ups,

etc.

¨

Knowledge

work takes place on unstructured documents. The opinion, however, must be

documented by person, Document categories, knowledge label, etc., to be

meaningful.

¨

Knowledge

work builds on collaboration. The organization structure must be flexible and

foster communities of interest to promote meaningful collaboration and opinion

evolution.

It would be safe to say the

knowledge worker is unaware of the next process step on an event till it is

taken. Knowledge work may take place within a work process at every process

step preceding action. As the following composite flow indicates, it determines

the work progress:

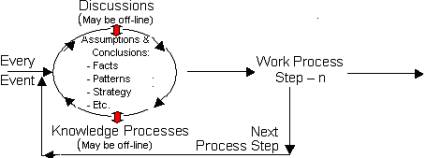

Fig. 1:

Composite mechanism. Action is taken

when a working conclusion is established

The IT Response – More Tools,

Platforms and Self-organization

The

leap in connectivity, storage, and processing power post 1993 gave IT the

potential to deliver the required mechanism for Knowledge Management. Email and search engines held promise

but suffered a limitation (Grove, 2001): “When it comes down to the bulk of knowledge work, the 21st century

works the same as the 20th century. You can reach people around the clock, but

they won’t think any better or any faster just because you’ve reached them

faster. The give and take remains a limiting factor”. Nonaka’s

revelation of the importance of tacit knowledge (Nonaka, 1991)

institutionalized incentives for sharing knowledge to overcome the

constraint. IT developed structures to solve specific problems where 50% of the

solution (Satyadas, 2003) relied on success of incentives. The KPMG surveys

indicate this to be a complex permanent commitment. It is possible incentive driven Give and Take does not inspire confidence (Balla, 2003) for the daily knowledge work since:

¨

Incentives

render Give and Take as separate discretionary acts, foreign to the daily work

process. Give is identified with document repositories instead of tacit

knowledge. Formal systems (Davenport, 1998) are needed to capture it. Isolated

Take is poorly internalized.

¨

Incentives

favor desires. Hence personnel are not protected from seeing what they wish to

see or from what they have time or the disposition to see or from the fear of

possibilities created by uncertainty. This is the Maya of Indian philosophy and

root cause of mistakes.

¨

Incentives

tend to create a passive culture (Pfeffer & Sutton, 2000) of briefings,

discussions, and planning sessions in which sounding smart is increasingly

rewarded in place of overcoming the knowing-doing gap for real world results.

IT’s failure to power an

autonomous mechanism for knowledge work has grave implications:

¨

Level-1: Possible consequences of poor work

experience that incentives cannot influence

o Low coordination on knowledge processes with ill-defined purpose and inadequate off-line support leads to absence of quality thinking time and stagnation of team-ability

o User-dependent time management and

downstream awareness leads to stakeholder anxiety

o Poor means for identity, purpose and

collective responsibility lower ability for risk and action

o Dependence on User to organize the

next process step imposes productivity limitation, and

o Poor accountability to counter

inertia for progressing action leads to “as we were”.

¨

Level-2: Sub-standard assimilation and use of knowledge

irrespective of success of incentives

o Reduction of knowledge work to Give

and Take leads to isolation instead of evolving opinion

o Dependence on discretion and effort

for Document creation make knowledge capture erratic

o The internalization of available

knowledge is poor since the understanding is not tested

o The knowing-doing gap remains

unaffected due misplaced emphasis on sharing per se

o Poor checks on wishful thinking or

mind sets – Maya – causes repeat mistakes, and

o Teams are unprepared for the improbable,

viz., are prey to complacency.

¨

Level-3: Anemic support, beyond the scope of

incentives, for visionary growth

o Poor awareness of the possible and

fuzzy goal definitions limits horizons, and

o Isolation leads to poor insights and

hence delayed or knee-jerk response to change.

¨

Level-4: Action to improve the Collective ability

has to be taken at a fundamental level

o

IT’s tools are not natural

to the work norms in use. Norms must change to improve ability.

It is clear that advance of

technology shall make little difference to team-ability till personnel

regularly use it for conducting knowledge processes. This requires automation

and perpetual availability since knowledge work is ubiquitous. However, the

conventional wisdom holds knowledge process automation to be impossible since

the next process step is unpredictable. Ray Ozzie (Weber, 2000), the creator

of group working, endorses the wisdom by conveying: “People work best when they can self-organize, cooperating spontaneously

in free-form ways”. Incentives fail to promote

adoption of IT’s tools with reason (Gartner, 2003): “... workers are

overloaded with an incoherent mix of tools and systems all purporting to

support their work activities, but designed and delivered without any composite

perspective of the work process."

Fig. 2:

Typical composite process as conceived by IT. Knowledge process is User-driven

not IT-driven

Fig. 2 shows IT’s emerging

approach of embedding collaboration tools in work processes. The approach will simplify

collaboration in context with a better sense of purpose. However, it neglects

the knowledge process serendipity and the need for off-line working. It retains

the key flaw of dependence on incentives for User-motivation to share tacit

knowledge and use IT for the purpose. It is possible IT hopes to change work norms

by leveraging the superior collaboration of the new approach and the urgent

need for a better knowledge mechanism.

Knowledge Management

Redefined: Knowledge Free-Flow

Conventional Knowledge

Management has degenerated into support systems and incentives for adoption of

IT’s tools to conduct knowledge processes, in its bid to harness the

extraordinary power of IT. This paper redefines Knowledge Management as

creation of a motivating, autonomous perpetual mechanism for purposeful

knowledge work in context to advance learning,

team-ability, governance and risk-taking, in particular, spark insights and

spur innovation. The following concepts presented over the years reveal the

facility required:

¨ Colonial success (Drucker, 1988, pp.

48): “..the best example of a large and successful information based

organization, and one without any middle management level at all, is the

British civil administration in India”. Regular asynchronous flow of assumptions

and conclusions in context was its foundation. Commitment to progress opinion

and deliver results ensured action. In free India the growth of hierarchies and

locations has introduced inertia.

¨

Spiral of knowledge (Nonaka, 1991, pp 97): “Articulation

and Internalization are critical steps in this spiral”, key to the success

of Japanese companies. Interaction of tacit and explicit knowledge redefines

premises to promote knowledge creation and organizational learning.

¨

Perpetual

Revolution (Peters, 1993): Tom Peters avers that “what counts” for

keeping complacency at bay and spurring innovation is a means to “mercilessly attack yourself”.

¨

Creative

Destruction (Foster & Kaplan, 2001): McKinsey studies of more than 1,000

corporations in 15 industries over 36 years establish that sustained

marketplace leadership requires corporations to continuously and creatively

reconstruct themselves.

The above concepts are

variants of the natural conduct of knowledge work depicted by Fig. 1. Open

debate, viz., enterprise wide free-flow of knowledge, is their unique common

feature. Success of knowledge communities, Ricardo Semler’s Semco (Semler,

2003) and the Silicon Valley experience (Meyer, 1997) demonstrate free-flow can be driven

by personnel self-interest like developing opinion, gaining recognition,

influencing action, collective responsibility, etc., for remarkable results. However,

free-flow is difficult to achieve. Semler’s norm reversal of giving up power

has been dismissed as maverick though it has demonstrated its success. Either

knowledge worker priorities (Davenport & Cantrell, 2002), viz., work norms,

or the conventional wisdom on knowledge process automation must change for

free-flow to succeed.

A Process For Free-Flow

Of Knowledge (Kumar, 2003)

The conventional wisdom’s

premise is that a one-size-fits-all knowledge process is impossible. My Science

Of Interactions (Kumar, 2003) normalizes all knowledge processes to one size

and provides the intelligence to conduct it. Briefly, Darwin’s Theory of Natural

Selection implies stable patterns evolve when many forces are at play. Teamwork

based on the flow of documents has evolved over centuries. It stands to reason

that a structure of parameters, norms and relationships has evolved to govern

how teams conduct their interactions in context to develop, manage and apply

knowledge. I have identified the structure by iteration. The major premises of

the Science are:

¨

Real

or virtual events progress an issue. They may be captured by Documents that

have a structured part to capture the organization reference using meta-data

such as Customer, Group, Pursuit, etc., and an unstructured part to capture

content.

¨

Knowledge maps,

with a common structure but unique to the enterprise’s work groups, relate the

meta-data of Documents. They make Document capture simple and rapid.

¨

Documents have

a life: creation followed by teamwork, collaboration, opinion formation, action

and archiving, all at personnel discretion. The State reflects the Document

status.

¨

18 repeatable

Actions assemble at least 90% of all actions taken on Documents. The balance

10% may be modeled using the same parameters. Action on a Document may lead to

an outstanding expectation. A Token controls right of Action.

¨

The Document

meta-data and any outstanding expectation are the primary determinants of the

Actions possible on it. The evolution of teamwork has established the norms

that govern the Actions possible on a Document. They are sensitive to the

Document State.

¨

The conversion

of knowledge to action has identifiable elements though the process loop is

unpredictable. The possible flow in Fig. 3 defines the elements of daily

decision-making on an event. The tacit knowledge heads may be used for labeling

knowledge capture.

Fig. 3:

A possible Knowledge to action conversion process

Fig. 4:

Document Workspace. Exists for each Document entry in the smart interface,

shown in Fig. 5, defined for each person. Screenshot shows the possible Action buttons

applicable to the Document. The Speak Action has been selected. The personnel

who qualify are shown for multiple selections. On OK, the expectation and

opinion are recorded and the nominee for follow-up is updated. Space for online

meeting is pre-defined

Using the tenets it becomes possible to create architecture to effortlessly

capture all multi-media unstructured events as Documents as shown in Fig.

4. Personnel may attend to them from a smart interface as shown in Fig. 5.

The interface organizes all Documents by centrally established categories and

offers the next possible Actions for execution as shown in Fig. 4. The figure

also shows the direct link from the Document to its opinion space vide Fig. 6.

Fig. 5:

Smart Interface. The categorization follows automatically from Document capture

and Action. Views provide for meaningful drill down. A Document workspace, shown in

Fig. 4, is defined for each Document in the interface. Note that the

interface gives the message on sight

Fig.

6: Opinion space for each Document linked to its workspace as shown in

Fig.4

The following are notable

features of the architecture for the smart interface:

¨

Document

Capture: The

taxonomy is defined for the organization per a framework that is common across

departments. The built in framework relationships capture Documents

effortlessly. The taxonomy aids the interface’s categorization of the pending

Documents.

¨

Knowledge

categorization: Fig.

3 illustrates that a broad understanding of the process is sufficient to create

labels for the knowledge exchanged to evolve superior judgment, do post-facto

analysis and reuse knowledge effectively. Only the relevant labels are

automatically offered, based on the Document meta-data, to update opinion.

¨

Tell-all

interface:

Categorizes for Users all the Documents-in-process across departments.

¨

Content: Token clearly defines

responsibility for progressing action and access rights to the Content.

Eliminates the need for conventional check in-check out to manage conflicts.

¨

Action:

The norms determine

the possible Actions that can be assembled in the Document workspace as shown

in Fig. 4, for effortless routing. The Actions can build any valid ad-hoc

composite flow as shown in Fig. 7. Note the categorization by expectation with

each Action. Where no expectation is pending a pre-mapped work process action

is permitted.

|

|

ß

Token possession

|

Fig. 7:

Spontaneous, unstructured workflow on a Document. Shows how Actions normalize

the knowledge process and transfer accountability. Parallel movements are also

possible

¨

Normalization: All knowledge flows can be

expressed in terms of the established categories (see Fig.5 & 6), the

possible Actions (see Fig. 7) and the knowledge labels (see Fig. 3). This

enables the interface to conduct and monitor any polyglot knowledge process.

¨

Collaboration: Space is defined for exchange in

context to form opinion. Members who do not possess the Token but are involved

may access the space to contribute.

¨

Opinion: Is normally contributed by the

Token holder. The space may be arranged as desired for prompt study. The

privacy, security and organization are preserved. Personnel with security

clearance may also study the evolution of opinion and contribute.

¨

Workflow

hooks: The system

is designed for ad-hoc flow in response to the knowledge process. Workflows may

be pre-defined under different Document Reasons. The smart interface offers an

icon to trigger action per the workflow map for the corresponding Reason,

specified at capture, when there is no pending expectation on the Document.

¨

Follow-Up: Special follow-up may be desired

both for Documents circulated internally and exchanged externally. A special

category called “Follow-Up” would be reported in Fig. 5. The User may

self-assign Follow-up or assign it to a team member.

¨

Roles: Personnel may hold multiple roles

with flexibility for rapid re-assignment.

¨

Routing: Sequential or parallel routing,

with or without transfer of responsibility follows from the Action selected.

Action integrated with the resource map for easy selection.

¨

Structure: The system supports a flexible

organization structure design that automatically re-routes the Documents in the

event of changes and imposes the revised security. Communities of interest are

created by the structure to promote expert advice or idea fertilization. The

flexibility encourages corporate re-structuring in response to the need.

¨

Security: It is determined in default by the

flexible organization structure and automatically specified by the routing. It

may be altered manually. Team members access the Document based on the roles

held by them and the security specified on the Document.

¨

Storage: The framework uniquely defines each

group’s storage space.

¨

Control: Where members are accountable for

an event, they have the option to transfer either the accountability or only

the responsibility for action on the Document. Where only the responsibility is

transferred, the Document may be recalled from downstream.

The interface is smart

because it organizes and anticipates the knowledge worker and intelligently

handles the following important activities among others from a single

interface:

¨ Dynamic cross-categorization of the interface (particularly by outstanding expectation) for swift review of action status and rapid drill-down. The interface resolves anxiety without imposing on team members for information, viz., it facilitates unobtrusive management;

¨ A natural way to share, develop and manage opinion and contribution in context, with accountability, even where the personnel are not in same-time contact;

¨

Either conducting pre-defined structured workflows

where permitted by the knowledge process or managing the exceptions that arise

in external workflow systems;

¨

Sparing the

User the following self-organization in conducting knowledge work:

o Intelligently aiding the creation and categorization of Documents on creation;

o Specifying security, circulation and recipient details each time an Action is taken;

o Storage of Documents and collaboration thereon across processes, departments and roles for easy review by desired indices;

o Aiding the next step on each Document and recording the expectation for pending status. The interface mitigates anxiety by providing the pending status on sight with drill-down;

o Creating follow-up records and assigning personnel for maintaining follow-up;

o Housekeeping the interface. Actions decide the archiving and category/status changes;

o Observing knowledge process rules while conducting workflow. E.g., refraining from forwarding a project to the next group while an internal query is pending;

¨ Search for experts for a given set of parameters;

¨ Conducting all work with means for prompt tracking and control of the chaotic progress of work on each Document. The chaos is managed and not eliminated. E.g., disallowing dispatch of a response Document where a new receipt has superseded its parent;

¨ Manage a two level categorized Knowledge repository: Level 1 provides event history and content, and Level 2 the flow of opinion on Level 1 as shown in Fig. 6; and

¨ Transparent access to all technology as needed by the User. The User need not bother about design of entry points, what technology to use, proper conduct of the process, creation and management of a community, etc. The smart interface offers a single window to handle the entire mechanics of the User’s work.

The smart interface harnesses IT to power the composite mechanism of Fig. 1 preserving the existing norms, i.e., it evolves the way of working. The way meets the communication needs of the virtual organization (HMCL, 2000). Its marvelous work experience assures its adoption (Kumar, 2003). Coordination and fully documented knowledge capture are by-products. Knowledge free-flow may be expected. However, the interface by itself only creates a portal.

Bmail – A Perpetual Mechanism For Free-Flow Of Knowledge

The seductive power of

email lies in its marvelous work experience for total satisfaction of the

personal communication need anytime and anywhere. The technology, however,

imposes for business communication over the intra/extranet and fails at

Knowledge Management. The email inbox requires the User to self-organize for

making sense, with poor downstream awareness and recall. It also does not capture the

expectation with which Documents are circulated or manage its own housekeeping.

In brief, it ignores the needs of knowledge work.

Group members may be

distributed across servers or may desire to work offline. The smart interface

needs to have email’s offline functionality to be a perpetual mechanism.

Replication technology is harnessed to provide this without imposing on the

User. Norms defined for the Actions are used to resolve all replication

conflicts that arise from Document sharing, e.g., cancellation of any

upstream Action deletes the Actions assembled downstream as also any content

development that may have taken place. In effect this overcomes the need for check

in-check out of Documents, with the Token concept playing a decisive role. The

replication not only refreshes the interface and Documents but may also be

tuned to refresh all reference Documents and related collaboration so that

personnel may function offline with full support.

Smart replication to

support anytime and anywhere knowledge work is a key component of the perpetual

mechanism. Any reliance on email for communication between interfaces shall

destroy the all important work experience. The facility has been christened

bmail since its primary function is the daily business communication over the

intra/extranet, and it promises the “seduction” email has for personal

communication. The intuitive way for performing the communication delivers the autonomous

perpetual knowledge mechanism as a by-product.

Conclusion

The present day collective

knowledge mechanism, supported by IT, requires the User’s energy for organizing

interaction and the next knowledge process step. The dependence is at least as old

as 300 BC. With the pace of change exceeding the mechanism’s knowing-doing

capacity, the collective falls prey to wishfulness, politics and inertia to

imperil decision-making. Drucker (1999, pp. 73) deems the response to change an

essential competence: “One cannot manage change. One can only be ahead of

it”. This makes the

vulnerability to hidden motives and inertia doubly unsafe, as risks must be

taken to lead change. Authoritative studies of corporate performance show

the way. The need is a better mechanism to develop and apply the collective

power for walking the way. Instituting incentives to use IT is not an answer.

They do not protect against the vulnerability, drain resources with unreliable

results and, instead of enabling better judgments and productivity, trivialize

knowledge work to ‘Give’ and ‘Take’.

The conventional wisdom

that a one-size-fits-all knowledge process is impossible has foiled IT’s past

attempts to upgrade the mechanism. Its current attempt is to change the work

norms with embedded tools. However, with dependence on the User to organize,

define purpose, share knowledge, imbibe learning and leverage IT, the new norms

shall increase the load on the old mechanism. Xerox (2001), at the forefront of

KM, exemplifies the impact. The restructuring time shrank and the leadership

was able to address personnel directly. The gain in ability was specific with

an energy burden. Personnel had to be trained and motivated to share

‘knowledge’, implying a process weakness to progress learning and mature action

on each event. Also, the new work norms required astute supervision to protect

natural sharing.

The Bmail concept manages

the knowledge worker instead of the knowledge processes. In principle, like FW

Taylor laid the foundations for the production assembly line, it identifies

repeatable knowledge work components for assembling knowledge processes. Its

smart interface uses norms and knowledge maps derived from the evolution of

teamwork to organize a categorized display of all work-in-process and

anticipate the next component on each event. Work processes may easily be

incorporated. Bmail harnesses IT to evolve, not change, the way of

communicating for a ‘seductive’ knowledge work experience offline and over the

intra/extranet. The organization acquires a reliable IT-conducted perpetual

mechanism to boost knowledge work productivity, create quiet thinking time,

improve response and induce a knowledge culture, i.e., dependable purposeful

free-flow with its creative destruction potential to pierce illusion, spark insights

and spur innovation. The leadership acquires autonomous means to galvanize

personnel for visionary growth. Chanakya noted in Arthashastra, his book on

statecraft written ~300 BC, that even a small rise in team-ability leads to enormous

gain.

Bmail seeks to offer an

irresistible knowledge mechanism for unifying and applying the knowledge of

people who may not see each other or interact at their convenience. It offers

this strength for vitalizing corporate life and building the future like

leading change or redefining purpose together with the structure to pursue it.

Changes in Bmail’s structure are capable of determining the organization’s

inherent capacities and behaviors like decision processing with the supply

chain or personnel participation level, etc. The leadership is liberated to ambition.

References

Balla, J.D. (July 2003)

Memoirs Of A Technocrat, Newsletter: DestinationKM.com, Steve Barth

http://www.destinationkm.com/articles/default.asp?ArticleID=1069

Ballard, R. (October, 2000)

Toward Knowledge Based Computing, DestinationKM.com, Steve Barth,

http://www.destinationkm.com/articles/default.asp?ArticleID=584

Buckman Labs (September,

2001) Mature Knowledge - Rumizen Melissie, DestinationKM.com, Steve Barth, http://www.destinationkm.com/articles/default.asp?ArticleID=354

Collins,

J.C., Porras, I.J. (1999) Built to Last: Successful Habits Of Visionary

Companies, Harper, New York

Cynefin (November, 2002) Rethinking

Management Methods-David Snowden, Steve Barth, DestinationKM.com, http://www.destinationkm.com/articles/default.asp?ArticleID=1013

Davenport, T.H.

(1998) Some Principles of Knowledge Management,

http://www.mccombs.utexas.edu/kman/kmprin.htm#political

Davenport,

T.H. (Nov, 1999) Knowledge Management - Round Two. CIO

Magazinehttp://www.cio.com/archive/110199_think.html

Davenport,

T.H. Cantrell S (January, 2002)

The Art of Work: Facilitating the Effectiveness of High-End Knowledge Workers, Outlook Journal, http://www.accenture.com/xd/xd.asp?it=enweb&xd=ideas%5Coutlook%5C1.2002%5Cart.xml

Dixon, N.M. (2000) Common

Knowledge, Harvard Business School Press, Cambridge

Drucker,

P.F. (Jan.-Feb., 1988) Coming of the New Organization, Harvard Business Review

Drucker, P.F. (1999)

Management Challenges for the 21st Century, Butterworth-Heinemann,

New York

El-Ghazali (12 AD)

as reported in The Way Of The Sufi, Idries Shah, Arkana, 1990

Foster, R., Kaplan, S.

(2001) Creative Destruction: Why Companies That Are Built to Last Underperform

the Market--And How to Successfully Transform Them, Doubleday, London

Gartner Research (2003), http://www-1.ibm.com/services/kcm/kcm_workplaces.html

Grove, A. (June, 2001) Is

Speed God Or The Devil, New

Thinking Newsletter, Govern GM http://www.gerrymcgovern.com/nt/2001/nt_2001_08_06_speed_god_devil.htm

HMCL (2000) Creating Successful Virtual Organizations, Newsletter from Harvard Business School Publishing, http://www.4cmg.com/InsideC/VirtOrg.htm

KPMG

(2002/3) European Knowledge Management Survey

http://www.knowledgeboard.com/download/1935/kpmg_kmsurvey_results_jan_2003.pdf

KPMG

(1999) Knowledge Management Research Report 2000, http://www.kpmg.nl/

Docs/Knowledge_Advisory_Services/KPMG%20KM%20Research%20Report%202000.pdf

Kumar R (August, 2003) Using IT To Assure A Culture For Success, Ajith Abraham et al.,

Proceedings of the Third International

Conference

on Intelligent Systems Design and Applications (ISDA'03), USA, Advances in Soft

Computing, Springer Verlag,

Germany,

2003,

Pg.353, http://www.cs.okstate.edu/~aa/isda03toc.pdf

Lao Tzu (~ 500 BC) Tao Te Ching, http://www.mountainman.com.au/tao_1_9.html

Meyer, C. (December, 1997)

Relentless Growth: How Silicon Valley Innovation Strategies Can Work, Your

Business, Free Press

Marcum,

D., Smith, S. (October, 2003) Making The Wrong Decisions, DestinationKM.com,

Steve Barth, http://www.destinationkm.com/articles/default.asp?ArticleID=1099

Naik, A.M. (September 2002)

Arthashastra, Lessons for Management Theory and Practice, The Bombay Chartered

Accountant Journal, http://esamskriti.com/html/inside.asp?cat=637&subcat=636&cname=arthashastra

Nonaka, I. (Nov.-Dec, 1991)

The Knowledge Creating Company, Harvard Business Review

Peters, T. (1993) The Case

For Perpetual Revolution, http://www.tompeters.com/toms_world/t1993/091093-case.asp

Pfeffer, J., Sutton, R.

(January 15, 2000) The Knowing-Doing Gap: How Smart Companies Turn Knowledge

into Action, Harvard Business School Press; 1st edition, Cambridge

Rabbi Salomon, Y. (September, 2001) The Day After,

aish.com http://www.aish.com/spirituality/growth/The_Day_After.asp

Satyadas, A. (March, 2003)

Growing a practical KM System, DestinationKM.com, Steve Barth, http://www.destinationkm.com/articles/default.asp?ArticleID=1036

Semler, R. (2003) The

Seven-Day Weekend. Random House, New

York

Senge, P.M. (original

release 1990) The Fifth Discipline, Currency, New York

Shepherd, M., Herring, D., Gutro, R., Huffman, G.,

Halverson, J. (2003), The Big Picture, www.weatherwise.com

Snowden, D. (Sept, 2000) The Organic Approach

to the Organization,

DestinationKM.com, Steve Barth, http://www.destinationkm.com/articles/default.asp?ArticleID=764

UNESCAP, What Is Good

Governance?, http://www.unescap.org/huset/gg/governance.htm

Weber, T.E. (November,

2000) “Peer-to-Peer” Connections Make A Smarter Internet, Wall Street Journal, http://groups.yahoo.com/group/launchpad-sv/message/1183?source=1

World Bank (May, 2001)

The Knowledge Bank - Denning S, Newsletter:

DestinationKM.com, Steve Barth http://www.destinationkm.com/articles/default.asp?ArticleID=541

Xerox (February, 2001), Can

KM Save the Document Company? – Anne Mulcahy, Steve Barth, DestinationKM.com, http://www.destinationkm.com/articles/default.asp?ArticleID=531

About the Author

Raj Kumar holds a Bachelors Degree in Mechanical Engineering from the Indian Institute Of Technology at Kanpur, India, and a Post Graduate Degree from the Indian Institute Of Management at Ahmedabad, India. He can be contacted as follows:

Raj Kumar, Director, Aim Knowledge Management Systems Pvt. Ltd., Badhwar

Park, Colaba, Mumbai – 400005, India Tel/Fax:

+91-22-22024898; Email: rajk@waykm.com;

URL: www.waykm.com