Knowledge Management Perceptions of Managers

Murat Gümüş, Bahattin Hamarat, School of Tourism & Hotel Management, Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart University

ABSTRACT:

This paper describes findings of perceptions of tourism managers on knowledge management level in Canakkale. Reviewing the literature on knowledge management, an empirical study was conducted via survey to seek how managers evaluate current knowledge level of their organizations. Items relating knowledge processes, enabling factors for knowledge management culture, technological and socio-cultural issues in organizations were formed. Thus, a holistic way of looking at knowledge management, especially putting the human factors before information technology was sought for.

Introduction

In a rapidly changing work

environment, organizations faces the challenge of how to manage its knowledge

assets effectively to generate market value and to gain competitive advantage.

The focus for knowledge influences everything concerning the organization such

as its strategy, products, processes and ways of organizing (Ruggles, 1997;

Martensson, 2000; Wiig, 1999). Thus, knowing what to manage as a knowledge is a

critical issue. Within this in mind, it is necessary to distinguish between

information and knowledge, between information management (IT) and knowledge

management (KM). Information can be anything that can be digitised, while

knowledge is the capacity to act effectively (Dawson, 2000). Consequently, IT

is the management of digitised information while KM includes IT plus all

aspects of how people are enabled in performing knowledge-based functions

(Dawson, 2000).

The debate on IT focused KM

and social/cultural focused KM spanning back to 1980s (Warne et al, 2003). Many

organisations invest in implementing information technology for providing

solutions to manage information resources and knowledge. The dominant picture

of knowledge management pays little attention to human and social factors

(Thomas et al, 2001). However,

paying less attention to people in knowledge processes will not make effective

differences. Studies show that less than 25% of IT investments integrate

business and technology objectives. In other saying, performance goals are not

achieved properly and the causes of such failure stem from the way people using

the technology and from the organizational factors (Warne et al, 2003). A study

of 431 US and European organisations, conducted by Ernst&Young Center for

business Innovation in 1997 (Ruggles, 1997; pp. 86-87) reveals that many

companies generally start with implementation of a technological capability

that will allow them to capture and share corporate know-how.

There is no relationship

between IT expenditures and company performance. This is because of the managerial

ignorance of the ways in which knowledge workers communicate and operate

through social processes of collaborating, sharing and building on each others’

ideas (Lang, 2001). People learn and with the interactions, a shared practice

is developed that contributes to the intellectual assets of the organisation,

due to Wenger (cited in Warne et al, 2003).

Knowledge is much more than

information and knowledge sharing is not an information sharing. Considering

the knowledge creation as an act of human being, knowledge management systems

must involve people and encourage them to think together and to take time to

articulate and share information and insights that will be useful to others in

their community. Managers must develop appreciation of the intangible human

assets captive in the minds and experiences of their knowledge workers (Lang,

2001). As McDermott quoted, “the great trap in knowledge management is using

information management tools and concepts to design knowledge management

systems” (1999; pp. 104).

Companies emphasize important technology and data infrastructure

initiatives, but organizational, cultural and strategic changes which are

necessary to leverage those investments is ignored or at least most of the

organizations fall in this category (Zack, 1999). For Demarest (1997), culture,

beliefs and actions of managers about the value, purpose and role of the

knowledge; creation, dissemination and use of knowledge within the firm; the

kind of expected strategic and commercial benefits of a firm; maturity of

knowledge systems; the way of organizing for knowledge; and the role of IT in

the KM program are six questions of effective participation in KM.

Socio-Cultural

Dimensions of Knowledge Management

Organisational culture

recognizing the value of knowledge allows personal contact that leads to

capture tacit knowledge and can be transferred (Davenport & Prusak, 1998).

“Values can not be shared electronically or via bits of papers” (Warne et al,

2003; pp. 94). For managing knowledge, effective management of technology and

social relations in firms is needed (Bhatt, 2000).

In a culture where the

knowledge value is recognised, availability of information, sharing of that

information, information flows, IT infrastructure, personal networking, system

thinking, leadership, communication climate, problem solving, training and many

other factors can be supportive factors for successful learning (Warne et al,

2003). For gaining an edge on KM, people – centered skills must be possessed

and be used constructively for nurturing and motivating people (Bhatt, 2000).

Knowledge is a human act;

is the residue of thinking; is created in the present moment; belongs to

communities; circulates through communication in many ways; and is created at

the boundaries of old, as McDermott describes (1999; pp. 105). Organizational

knowledge is social in character. Firms organize and cultivate knowledge to

develop core competency or know-how (implicit), and own ability to put know-what

(explicit) into practice (Lang, 2001).

Some Of The Basic

Factors For Effective KM

For successful and viable

outcomes of knowledge management, many factors may play important roles.

However, some of those are out of influence of the organization while some are internal

and can be arranged. Ability to deliver desired service paradigms, ability to

act timely, capabilities of employees, innovativeness, work levels links to

strategy and direction, ability to creat, ability to solve unexpected issues,

effectiveness of enterprise systems, procedures and policies are some of those

factors (Wiig, 1999).

The role of culture

Culture plays an important

role in how KM function is being implemented in organizations Smith & McKeen,

2003). As McDermott (1999) notes, four KM challenges domain involves human

interactions. These are technical, social, managerial and personal. The sum

total of individual knowledge can be collective knowledge by developing a

culture that values knowledge sharing and knowledge creation. It is accepted

that organisational learning culture is important for knowledge creation

(Bhatt, 2000).

KM Processes

Considering the

process-based view of management theory, major categories of knowledge- focused

activities can be an answer for what can be managed about knowledge (Ruggles,

1995; pp. 81; Probst et al, 2000; Powers, 1999):

¨

Generating/creating

new knowledge,

¨

Accessing

valuable knowledge from outside sources

¨

Using

accessible knowledge in decision making

¨

Embedding

knowledge in processes, products and/or services

¨

Representing

knowledge in documents, databases and software

¨

Facilitating

knowledge growth through culture and incentives

¨

Transferring

existing knowledge into other parts of the organization

¨

Measuring

the value of knowledge assets and/or impacts of knowledge management

Knowledge creation

The most important aspect

of a knowledge management system is the “knowledge community” (Thomas et al,

2001). Knowledge creation can be possible in a shared space for emerging

relationships. In other word, for Nonaka and Konno, “ba” or space that may be

physical, virtual, mental or any combination of those provides a platform for

advancing individual and collective knowledge (1998). If knowledge is separated

from ba/place, it turns into information, which can then be communicated

independently from ba. Information is tangible and resides in media and

networks, however knowledge is intangible and resides in ba (Nonaka &

Konno, 1998). The effective creation of new knowledge, especially tacit

knowledge, hinges on strong caring relationships among the members of an

organization (Lang, 2001). Sharing tacit knowledge can be possible through

joint activities such as being together, spending time, living in the same

environment, known as socialization stage for knowledge conversion (Nonaka

& Konno, 1998). Knowledge management efforts must focus more on tacit

knowledge and experiment with new organizational forms, cultures and reward

systems to enhance interpersonal interaction and social relationships (Lang,

2001). Human relationships are themselves a function of the organizational

culture (Lang, 2001).

Leadership

Knowledge is manageable

only when leaders embrace and foster the dynamism of knowledge creation. Top

management acts as the providers of “ba” for knowledge creation (Nonaka &

Konno, 1998). Lack of support from senior management, specifically visionary,

moral and fiscal resources, KM efforts cannot be successful. Top management

must realise that knowledge needs to be nurtured, supported, enhanced and cared

for. What they should consider for enabling knowledge creation is to think in

terms of systems and ecologies which can provide for the creation of platforms

and cultures where knowledge can freely emerge (Nonaka & Konno, 1998).

Learning &

Participation

Learning cannot be limited

to acquire facts and techniques. People learn through participation in

communities of knowledge by embodying their particular perspectives, prejudices

and practices. Knowledge work is dominated communication, deliberation, debate

and negotiation. Knowledge is created as practitioners see the logic of each

other’s thinking in communities who have common interests (Lang, 2001). To

facilitate learning, the culture of the organization must nurture a climate

within which learning and knowledge are highly valued, empowerment of

individuals, motivation to questions are required. Leadership is crucial for

such a culture. Building trust to encourage sharing and experiential learning

of tacit knowledge is the responsibility of leadership (Stonehouse &

Pemberton, 1999). For achieving KM benefits, a corporate learning strategy

should be developed (Coulson-Thomas, 2000)

Strategy

Knowledge management

efforts lack of strategy link and even it is not a key evaluation criterion or

motivating factor (Ruggles, 1997). Decisions are made in a context including a

business strategy along with a set of experiences and skills, a culture and

structure, and a set of technology and data. In an organization, in creating

value, people can use their competence externally or internally. External

structure consists of relationships with customers, suppliers and the image of

the firm. Internal structure consists of patents, concepts, computer,

administrative systems, models. Internal networks culture also belongs to the

internal structure (Sveiby, 2000).

Successful knowledge

strategies can be as those: explicit and clear links to business strategy-

value adding knowledge; knowledgeable about knowledge; a compelling vision;

knowledge leadership; systematic knowledge processes as capturing

external/internal knowledge, organizing and sharing knowledge; well-developed

knowledge infrastructure; appropriate bottom line measures-i.e. measuring

knowledge contribution (Skyrme, 1998).

Knowledge To Be Managed

Business organizations view

knowledge as their most valuable and strategic resources. To remain

competitive, they know that they must manage their intellectual resources and

capabilities. Integrated focus of technical and organizational initiatives

together –i.e. IT-supported KM (Gottschalk, 1999) can provide a comprehensive

infrastructure to support KM processes, but it is not the guarantee for

investments and objectives of the firms (Zack, 1999). A knowledge strategy is

needed to fulfil the mission to strengthen competitive position and to create

shareholder value. Knowledge management must linked to the creation of economic

value and competitive advantage (Zack, 1999). Organizations must strategically

assess their knowledge resources and capabilities. What they know and what they

must know are the crucial starting point to play the game. Every firm’s

strategic knowledge can be categorised by its ability to support a competitive

position. There can be core knowledge, advanced knowledge (competitive

viability) and innovative knowledge (leading leadership of the industry) (Zack,

1999). An understanding of the knowledge nature is imperative, allowing the

environment which is supportive for the generation of knowledge, storage,

coordination and diffusion, thus resulting in a core competence influencing

competitive advantage (Stonehouse & Pemberton, 1999). Competitive advantage

is based on firm specific core competences (Prahalad & Hamel, 1990). Core

competences are combinations of resources and capabilities unique to a specific

organization and generating competitive advantage by creating unique customer

value. Core competences may be based upon knowledge of customers, knowledge of

technology, knowledge of processes, and etc. (Stonehouse & Pemberton,

1999). An organization’s effectiveness at its core knowledge processes depends

on its capabilities of dealing with knowledge- i.e. knowledge capabilities. For

developing knowledge capabilities, individual and organizational technology,

individual and organizational skills and behaviours must be addressed (Dawson,

2000). Converting knowledge into core competence and competitive advantage

essentially depends on sharing and co-ordinating knowledge within the

organization and with collaborating businesses (Stonehouse & Pemberton,

1999). As the result, knowledge management should be linked to the building

blocks of it, namely, mission, structure, culture, strategy, style of

management, personnel, systems and finally the instruments used to manage the

tacit and explicit knowledge (Beijerse, 1999). As an answer to question of what

kind of knowledge to be managed is the knowledge that is usable those are

current (strategy and performance in terms of existing and potential), relevant

(What is in it for me?) and actionable (concerning processes) (Bailey &

Clarke, 2001). In other word, to manage knowledge successfully, a cultural,

organizational and technical infrastructures that enable knowledge process to

take place are required (Demarest, 1997).

Research Methodology

Considering the literature

debates on KM, the goal of this study is to investigate KM perceptions of

tourism managers in Canakkale. The basic research method of the study was a

face-to- face survey of managers selected from the population.

Since tourism activities

are primarily service works that require quicker, flexible solutions because of

its human-intensive nature on each side- i.e. service frontiers contacts with

consumers, competences of personnel can make differences. However, without

enabling factors, a person cannot make difference at great amount in

serving. So, organizational

culture that serves them to make better will definitely be fundamental enabler

for successful service. A well -equipped and competent person can make

difference this time.

For the reasons concerning

tourism works given above, tourism managers were targeted as they were the

providers of the knowledge management system in those organizations. Since

there were only few travel agents in the region, agents were not included in

the research sample. Managers from hospitality firms and food & beverage

firms were surveyed. 21 items were developed concerning KM and responses were

asked in 5 points likert-type, ranging from 1 (totally agree) to 5 (totally

disagree). Meanwhile, managerial position, gender and level of education were asked in a structured form.

Managers filled in questionnaire forms at their sites in face- to- face

context.

Considering the literature

review, four KM categories were created. One of them is directional that

give way organization to have its route as competitive focus, competitive use,

customer focus and strategic focus. Cultural category includes creative,

innovative and learning perspectives. Since learning is an human act, the third

category was labelled as human resource issues, including IT training,

teamwork and participation, communication, education and orientation. And

finally, to see how the knowledge is embedded in processes of knowledge, process

category including access, storage, use and share of knowledge was considered.

The frequencies of all the variables, sub-categories of the variables and

explanation of all the abbreviations used in the analysis are given in Table I.

The reliability of the items is

0,8417 (alpha coefficient) indicating high reliability.

In the study, to present a

clearer graphical map, 5-point Likert response categories were recoded and

reduced to three categories as agree, partly agree and disagree, and only

two-dimensional solutions were used. The obtained data were analysed in SPSS

Package Version 8.0 that contains PRINCALS version 0.6.

Analysis

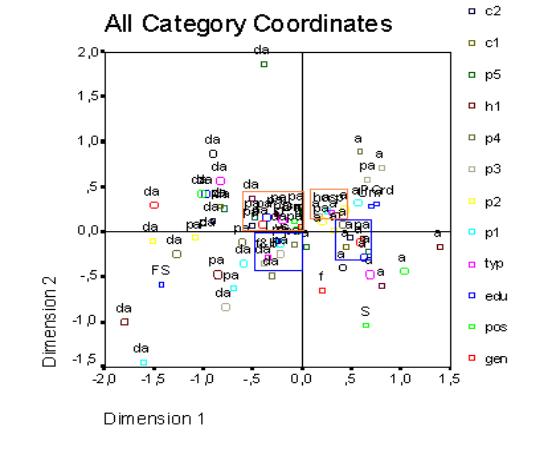

For the purpose of the study, non-linear principal components analysis (PRINCALS) was conducted to see the relationships among variables assuming the relationships as non-linear. As it is known, PRINCALS allows to treat variables as numeric, ordinal or nominal variables (Konig, 2002; Michailidis, 1996).

“Non-linear principal

components analysis searches for an optimal mean squared correlation between

the variables recoded by the category quantifications, and the components. In

the search for optimal mean correlations between the recoded variables and the

components, both the component loadings and the category quantifications are

varied until the optimum is found” (Konig, 2002; pp. 116).

Briefly, PRINCALS is a

non-linear technique for detecting relationship within a group of numerical or

categorical variables (Heijltjes & van Witteloostuijn). It stands for

“PRINcipal Component Analysis by means of alternating Least Squares” and was

set forth first by Rijckevorsel and de Leew in 1979. It has a wider range of

application since it allows not only nominal variables, but also ordinal and

numerical variables. It can also treat nominal variables with single or

multiple quantification (Van de Geer, 1993). On the other hand, as Gifi (1991)

mentioned, PRINCALS accepts multiple nominal since it is based on meet loss,

whereas other programs are based on join loss. The relationship between

variables is assumed as non-linear. Data to be used in the analysis should be

positive. Zero or minus values are not considered in the analysis. Moreover,

only one set of variable is used. In the case of more than one set of

variables, non-linear canonical correlation analysis (OVERALS) is used.

PRINCALS allows graphical display of considered variables on a two-dimensional

map. Objects of the same category locate closer whereas objects of the

different categories locate in far distance.

Results

Eigenvalue for dimension 1

and dimension 2 are 0,23 and 0,08 respectively. These eigenvalues can be

interpreted as the square of canonical coefficients between object scores and

optimally quantified variables in the case where no missing data exist. However,

the above given eigenvalues are not so strong for total fit. Component loadings

for the whole variables are presented in Table-II numerically and in Figure–1

graphically. Component loadings show correlations between object scores and

rotated variables. Gender (Gen) and Type (Typ) were found as located at the

centre. Component loadings located on first dimension were found to be

negatively loaded except Position (Pos) and Education (Edu). Component loadings

show that the higher the value on a dimension the better the variable is

weighted on that dimension.

Table I: Frequency of Categories for

Demographic and Perception Variables

|

Variable* Categories** |

Variable

Categories |

|

1 2 3 4 |

1 2 3 4 |

|

GENDER 92 8 POSITION 65 24 11 EDU

5 63 29 3 TYPE 55 45 p1

76

21

3 p2

78

20

2 p3

13

22 65 p4

30

20 50 h1

4

19 77 p5

76

20

4 c1

65

31

4 c2 53 42 5 p6

30

47 23 h2

46

39 15 |

d1 85 11 4 h3 47 43 10 d2 51 40 9 p7 22 59 19 d3 44 45 11 p8 33 52 15 h4 37 45 18 h5 29 37 34 h6 67 27 6 d4 63 32 5 c3 74 24 2 |

*Categories

for each variables are as follows:

Gender

(male,female)

Position

(General Manager, Departmental Manager,Superviser)

Education

(First and secondary, Lycee, University, Post graduate)

Type

(Hospitality, Food&Beverage)

For

all KM variables (agree, partly agree, disagree)

*P denotes process items: P1

access, p2 storage, p3 use of knowledge, p4 share,

p5 access, p6 measure, p7

use of knowledge, p8 use of knowledge.

H denotes human factor items: h1 IT training,

h2 teamwork, h3 communication,h4 education, h5 orientation, h6 voluntary

participation.

C denotes culture items: c1

creative culture, c2 learning culture, c3 innovative culture.

D denotes direction items: d1 customer focus, d2 competitive focus, d3

competitive use, d4 strategic focus.

Table II: Component Loadings

|

Variable Dimension 1 2 |

Variable Dimension

1

2 |

Variable Dimension 1 2 |

|

GENDER - - POSITION ,231 -,362 EDU ,551 ,226 TYPE - - p1

-,483 -,433 p2

-,604 -,036 p3

-,530 -,467 p4

-,389 -,601 h1

-,435 ,049 |

p5

-,088 ,413 c1 -,608 ,212 c2

-,521 ,069 p6

-,537 ,397 h2

-,628 ,205 d1

-,401 -,019 h3

-,426 ,411 d2

-,669 ,133 |

p7 -,661 ,276 d3 -,583 ,258 p8 -,533 ,364 h4 -,447 -,258 h5 -,437 -,248 h6 -,258 -,274 d4 -,554 -,104 c3 -,565 -,311 |

Components loadings p2, c1, c2, p6, h2, d2, p7, d3, p8, d4 and c3 are represented better by dimension 1, and p4 is represented better by dimension 2 while p1, p3, h3 and h6 variables are represented by both dimensions. On the other hand, p1, p2, p3, p4, d1, h4, h5, h6, d4, and c3 variables were found to have same directions and closely correlated. h1, p5, c1, c2, p6, h2, h3, d2, p7, d3 and p8 variables were found as being changing in the same directions together.

Figure 1: Components Loadings for Variables

Figure 2: Perceptions of Managers Due to Sub Categories of The Variables

In order to determine homogenous groups of tourism managers due to their perceptions about sub categories of variables, PRINCALS was conducted. Groups formed were presented in Figure 2, graphically, and their coordinates on the dimensions were given in Table III, numerically. As it can be seen, four homogenous groups were obtained. The formation of groups were set according to the responses of the participants. In other word, the relationship between the sub-categories of variables and the sub-categories of knowledge management items given in the questionnaire has determined the formation of the groups. These groups are as follows. The first group or cluster consists of p5 (pa and da), p6 (pa and da), p7 (pa), p8 (pa), c2 (pa), h1(da), h2 (pa), h3 (pa), d2 (pa) and d3 (pa) . The second cluster consists of p3 (da), p4 (pa and da), h4 (pa and da), h5 (da) and h6 (pa) . The third cluster consists of p1 (a), p2 (a), d1 (a), d4 (a), h5 (a and pa), h6 (a) and c3 (a). The fourth one consists of p5 (a), d2 (a), d3 (a), c1 (a), c2 (a), h1 (pa), h2 (a) and h3 (a).

The first group shows that knowledge access, measuring, use of knowledge, learning culture, IT use training, teamwork, communication, competitive focus and competitive use of knowledge form a group having partly agreement and disagreement which means that lack of these factors come together that may support the third and the fourth group formation. The second group shows that IT use, knowledge sharing, education, orientation and voluntary participation come together with their partly agreement or disagreement which also support the third and the fourth group formation result. These two groups can be combined to have one group since both groups have similar perceptions concerning the mentioned variables (left hand-side of Figure-2).

The third group shows that knowledge access, storage, customer focus, strategic focus, personnel orientation, voluntary participation, innovative organizational culture are available in organizations. The fourth group shows that knowledge access, competitive focus, competitive use of the knowledge, creative and learning culture, IT use training, teamwork and communication factors co-exist in these organizations. Combining these two groups may be more meaningful to explain the existences of effective knowledge management level( right hand-side of Figure-2).

Table III. Category Coordinates for Variables

|

Variables |

D1 |

D2 |

Variables |

D1 |

D2 |

Variables |

D1 |

D2 |

|

Pos Gm Dm S |

-,08 -,08 ,66 |

,13 ,13 -1,03 |

c1 a pa da |

,45 -,83 -,83 |

-,16 ,29 ,29 |

d3 a pa da |

,62 -,37 -,98 |

-,28 ,16 ,43 |

|

Edu Fs Lyc Univ PGrd |

-1,43 -,25 ,71 ,76 |

-,59 -,10 ,29 ,31 |

c2 a pa da |

,48 -,50 -,91 |

-,06 ,07 ,12 |

p8 a pa da |

,69 -,20 -,83 |

-,47 ,14 ,57 |

|

p1 a pa da |

,26 -,70 -1,62 |

,23 -,63 -1,45 |

p6 a pa da |

,81 -,27 -,51 |

-,60 ,20 ,38 |

h4 a pa da |

,56 -,22 -,60 |

,32 -,13 -,34 |

|

p2 a pa da |

,32 -1,09 -1,53 |

,02 -,07 -,09 |

h2 a pa da |

,67 -,49 -,80 |

-,22 ,16 ,26 |

h5 a pa da |

,44 ,20 -,59 |

,25 ,12 -,34 |

|

p3 a pa da |

,81 ,67 -,39 |

,71 ,59 -,34 |

d1 a pa da |

,17 -,95 -,95 |

,01 -,05 -,05 |

h6 a pa da |

,16 -,22 -,78 |

,17 -,23 -,83 |

|

p4 a pa da |

,58 ,09 -,31 |

,90 -,14 -,48 |

h3 a pa da |

,40 -,23 -,90 |

-,39 ,22 ,87 |

d4 a pa da |

,41 -,61 -1,28 |

,08 -,11 -,24 |

|

h1 a pa da |

1,39 ,62 -,22 |

-,16 -,07 ,03 |

d2 a pa da |

,59 -,41 -1,51 |

-,12 ,08 ,30 |

c3 a pa da |

,33 -,85 -1,81 |

,18 -,47 -,99 |

|

p5 a pa da |

,03 -,05 -,40 |

-,16 ,24 1,87 |

p7 a pa da |

1,04 -,06 -1,02 |

-,43 ,02 ,43 |

|

|

|

.Conclusions

In this study we have

firstly presented the literature debates on IT-focused KM and cultural KM. In a

next step, we conducted a survey containing items about KM- related factors as

process, direction, human resource and culture. It was expected to see the

level of overall KM perceptions of tourism managers in a narrower geographical

area where the competition is not so intense. Tourism managers should keep in

mind that tourists possibly faces higher level service offerings in more

competitive destinations before coming to this site. On the other hand, in a globalised

world, the expectations of both parts are influenced greatly. Thus, the perceptions of managers at all

levels in organizations concerning knowledge and knowledge management factors

will give directions to better level for exploitation and exploration of

knowledge management.

Looking at the results of

the research, we see that two distinct groups form heterogeneously, or four

groups forms homogeneously according to the perceptions of managers. Managers

who agree that the given expressions or statements are valid for their

organizations form a group (third and fourth groups). Agreement category

include knowledge access, knowledge storage in terms of process, innovative

culture, creative culture and learning culture in terms of culture, strategic

focus, customer orientation, competitive focus and competitive use of knowledge

in terms of direction, and finally participation and teamwork, training,

communication in terms of human resource perspective. However, managers who

partly agree on orientation also fall in this group. On the other hand,

managers who disagree on training, use of knowledge, orientation and managers

who partly agree on use of knowledge, learning culture, teamwork,

participation, communication, competitive focus and competitive knowledge use

form a group.

An other important finding

of this study is that general managers and middle level managers due to their

organizational position take part in group where partly agreement and

disagreement are grouped. Supervisors on the other hand as a position

sub-category stands far from each group. In terms of education, Lycee level

take part in group 2. Graduate and post-graduate level stand near third group

but is located out of it. Primary and secondary education levels also stand far

from each groups. Meanwhile, as mentioned before, gender and firm type locate

at the centre.

The ,most iomportant

results from this study can be concluded as the following:

Gender makes no difference

and doesn’t play important role on the knowledge management perception of managers.

Type of tourism firm as hospitality and food & beverage also makes no

difference on the perception of managers.

Perception of supervisors

is different from general managers and departmental managers. This means that

managerial position plays role on perceptions. This can be the sign of weak

knowledge culture.

Managers who are agree on

knowledge management dimensions in their firms form a group, however some of

the dimensions, namely the knowledge measurement, use of knowledge, knowledge

sharing and education are excluded. In other word, managers who are agree on

these dimension are not homogeneous with the managers those agreeing on other

dimensions. Indeed, this finding is not congruent with the previous theoretical

assumptions.

As a final word, tourism

managers of Canakkale generally are aware of knowledge management factors. This

can be seen as the entrance step to make a change in their firms to benefit

from knowledge management since the human and cultural side of knowledge

management is very crucial in service firms and specifically in tourism firms.

References

Bailey, C. & Clarke, M.

(2001), “Managing knowledge for personal and organisational benefit”, Journal

of Knowledge Management, Vol.5, No.1, pp.58-67.

Beijerse, R. P. (1999),

“Questions in knowledge management: defining and conceptualising a phenomenon”,

Journal of Knowledge Management, Vol.3, No.2, pp.94-109.

Bhatt, G.D. (2000),

Information dynamics, learning and knowledge creation in organizations”, The

Learning Organization, Vol.7, No.2, pp.89-98.

Coulson-Thomas, C. (2000),

“Developing a corporate learning strategy”, Industrial and Commercial Training,

Vol.32, No.3, pp.84-88.

Davenport, T.H. &

Prusack, L. (1998), Working Knowledge: How organizations manage what they know,

Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Demarest, M. (1997),

“Understanding knowledge management”, Long Range Planning, Vol.30, No.3,

pp.374-384.

Dawson, R. (2000),

“Knowledge capabilities as the focus of organisational development and

strategy”, Journal of Knowledge Management, Vol.4, No.4, pp.320-327

Gottschalk, P. (1999), “Use

of IT for Knowledge Management in Law Firms”, The Journal of Information, Law

and Technology (JILT), http://elj.warwick.ac.uk/jilt99-3/gottschalk.html.

Gifi, A. (1991), Nonlinear

Multivariate Analysis, England: John Wiley & Sons.

Heijltjes, M.G. & van

Witteloostuijn, A. “Configuration of Market Environments, Competitive

Strategies, Manufacturing Technologies and Human Resource Management Policies”,

NIBOR/RM/96/07, Available at http://www.edocs.unimaas.nl/files/nib96007.pdf.

Konig, R. (2002), “On the

rotation of non-linear principal components analysis (PRINCALS) solutions:

Description of a procedure”, ZUMA-Nachrichten 50.jg.26, pp.114-120.

Lang, J.C. (2001),

“Managerial concerns in knowledge management”, Journal of Knowledge Management,

Vol.5, No.1, pp.43-57.

Martensson, M. (2000), “A

critical review of knowledge management as a management tool”, Journal of

Knowledge Management, Vol.4, No.3, pp.204-215.

McDermott, R. (1999), “Why

information technology inspired but cannot deliver knowledge management”,

California Management Review, Vol.41, No. 4, pp.103-117.

Michailidis, G. (1996)

“Multilevel Homogenity Analysis”, Theses &. Dissertations, Paper No.2, UCLA

Statistics Program, http://www.stat.ucla.edu/thesis/index_body.php. Consulted in October 2003.

Nonaka, I. & Konno, N.

(1998), “The Concept of “Ba”: Building a Foundation For Knowledge Creation”,

California Management Review, Vol.40, No.3, pp.40-54.

Powers, V.J. (1999), “Xerox

Creates a Knowledge-Sharing Culture Through Grassroots Efforts”, Knowledge

Management in Practice, No.18, pp.1-4.

Probst, G., Raub, S. &

Romhardt, K. (2000), Managing Knowledge- Building Blocks for Success, West

Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Prahalad, C.K. & Hamel,

G. (1990), “The core competence of the corporation”, Harvard Business Review,

May-June, pp.79-91.

Ruggles, R. (1997), “The

State of the Notion: Knowledge Management in Practice”, California Management

Review, Vol.40, No.3, pp.80-89.

Skyrme, D.J. (1998),

“Developing Knowledge Strategy”, URL: Available (20 July 2003) at http://www.skyrme.com/pubs/knwstrat.htm

Smith, H.A. & McKeen,

J.D. (2003), “Knowledge Management in Organizations: the State of Current Practice”,

KBE Queen’s Centre for Knowledge-based Enterprises, Working Paper, WP 03-02,

Ontario.

Stonehouse, G.H. &

Pemberton, J.D. (1999), “Learning and knowledge management in the intelligent

organisation”, Vol.7, No.5, pp.131-139.

Sveiby, K-E (4/12/ 2000),

“A Knowledge-based Theory of the Firm to Guide Strategy Formulation”, paper

presented at ANZAM Conference, Macquaire University, Sydney;

http://www.sveiby.com.au/knowledgetheoryoffirm.htm

Thomas, J.C., Kellogg, W.A.

& Erickson, T. (2001), “The knowledge management puzzle: Human and social

factors in knowledge management”, IBM Systems Journal, Vol.40, No.4,

pp.863-884.

Van de Geer, J.P. (1993),

Multivariate Analysis of Categorical Data: Theory, California: Sage Pub.

Warne, L., Ali, I.M. &

Pascoe, C. (2003), “Team Building as a Foundation for Knowledge Management:

Findings from Research into Social Learning in the Australian Defence

Organization”, Journal of Information & Knowledge Management, Vol.2, No.2,

pp.93-106.

Wiig, K.M. (1999), “What

future knowledge management users may expect”, Journal of Knowledge Management,

Vol.3, No.2, pp.155-165.

Zack, M.H. (1999),

“Developing a Knowledge Strategy”, California Management Review, Vol. 41, No.3,

pp.125-145.

About the Authors:

Assist. Prof. Murat GÜMÜŞ received

his B.S. in Communication Arts from Anadolu University, Eskişehir, and became a research assistant at

Canakkale Onsekiz Mart University in 1993. He received his Master of Management

& Organization, and his Ph.D. of Business Administration from Uludağ

University, Bursa. He promoted as Assistant Prof. In 2001. His study topics are

Organizational Behavior, Knowledge Management, Intercultural Communication, and

TQM.

Assist. Prof. Murat GÜMÜŞ, Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart University, School of Tourism & Hotel

Management, Terzioglu Campus, 17100, Canakkale/ Turkey; Phone:+90-286-218 00 18

(1486)/ 0535-4509427 (GSM); e-mail: muratgumus@yahoo.com or mgumus@comu.edu.tr

Lecturer Bahattin HAMARAT received

his B.S. and Master of Science in Statistics at Anadolu University, Eskişehir.

He attended to the same university as lecturer. He then moved to Canakkale

Onsekiz Mart University as a lecturer.

Lecturer Bahattin HAMARAT, Çanakkale

Onsekiz Mart University, School of

Tourism & Hotel Management, Terzioglu Campus, 17100, Canakkale/ Turkey; Phone:+90-286-218

00 18 (1431); e-mail: bhamarat@comu.edu.tr